Happy New Year!

Author – 周尚, Zhou Shang

The scenery outside the window swept by, and some unmelted snow lay lazily in the shade of the trees. The wind also took off a few withered yellow leaves and ran away by itself. The friction between the wheels and the rails gradually subsided. Standing on the platform, even the air was full of joy. At this time, there will always be unspeakable emotions pushing tears out, half thinking about finally returning to my hometown, and half thinking that the four seasons have finally finished changing shifts and have started a new round.

For Chinese people, the New Year is red, like the rising sun, bringing light into thousands of households and shining on the next round of four seasons; like a new life, flowing bright red blood, with incomparable vitality. When I first returned to my home in Nanjing, my home was still old, with white walls and black bricks, green trees and blue sky, and everything seemed serious and indifferent. This is not in line with the New Year’s atmosphere.

So under the two osmanthus trees facing the window, I brought a ladder, picked up a longer branch, stuck the small lantern on the branch first, then found a branch between the leaves, picked up the lantern and hung it on it. After a lot of effort, the whole tree was finally covered with small lanterns, as if a string of red fruits had grown.

As the saying goes, “Thousands of families are in the sun, always replace the new peaches with old charms”. The two sides of the gate should be pasted with Spring Festival couplets. People dip in ink and write on the red paper what they hope for the next year. Stick it next to the door god. It is always a happy experience to enter and go out. In Chinese, “inverted” and “to” are homophonic, so the word “fu” in the middle of the gate or on the window is always pasted upside down, which means: ‘lucky arrival’. With the last window flower pasted on the window, the home finally seemed to be ready for the Spring Festival.

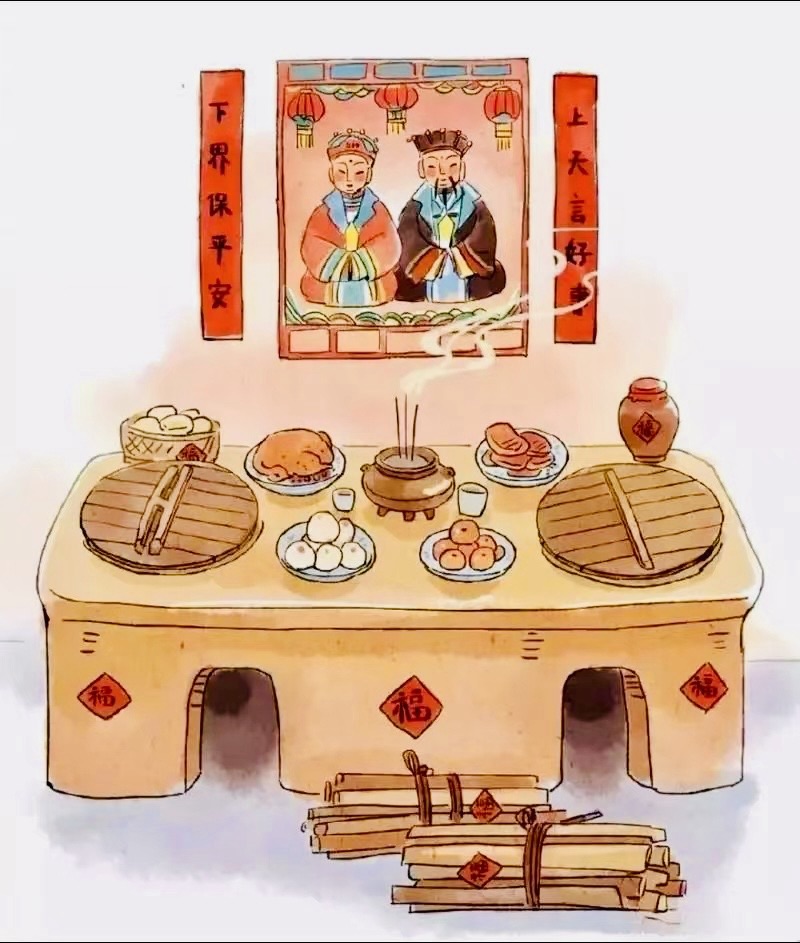

It’s the New Year in a blink of an eye. This day of the New Year is to pay tribute to the Kitchen Lord. It is said that the Kitchen Kord of each family will return to heaven on this day to report the good and bad things that people have done in this year. When I get up early in the morning, I follow my parents to clean the stove, put incense in the incense burner in the middle of the two stoves, and then put two plates of bright fruit on both sides. When I was a child, my grandmother also told me an anecdote: Hongwu Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang was poor when he was a child and could not afford meat to eat. He found a meat seller during the Spring Festival, hoping he can give him a piece of meat to eat. When the shopkeeper saw where the wild boy came from, he opened his mouth and asked him to go outside. Then Zhu Yuanzhang said that if no one wanted the pig’s head, he would take it. The boss still drove him away. Therefore, Zhu Yuanzhang shouted to the boss that he would become emperor in the future. Later, when he became emperor, he decreed that he would add another year to the calendar, but the distance between the north and the south was different, so there was a difference of one day. But it’s just an anecdote. Emperor Hongwu ascended the throne in Yingtianfu, which is today’s Nanjing. If the story is really as it says, how can he notify the north first and then the south?

In Nanjing, Jinling, we will make a special dish during the Spring Festival, which is a stir-fry with 16 to 19 kinds of vegetables such as cauliflower, snow berry, soybean sprouts, etc., which are called ten kinds of dishes, also known as assorted dishes. Each vegetable tastes different, and the order of cooking is different. The whole family work hard together on the cooking, which shows the moral meaning of such a dish : “peaceful and long-lasting”.

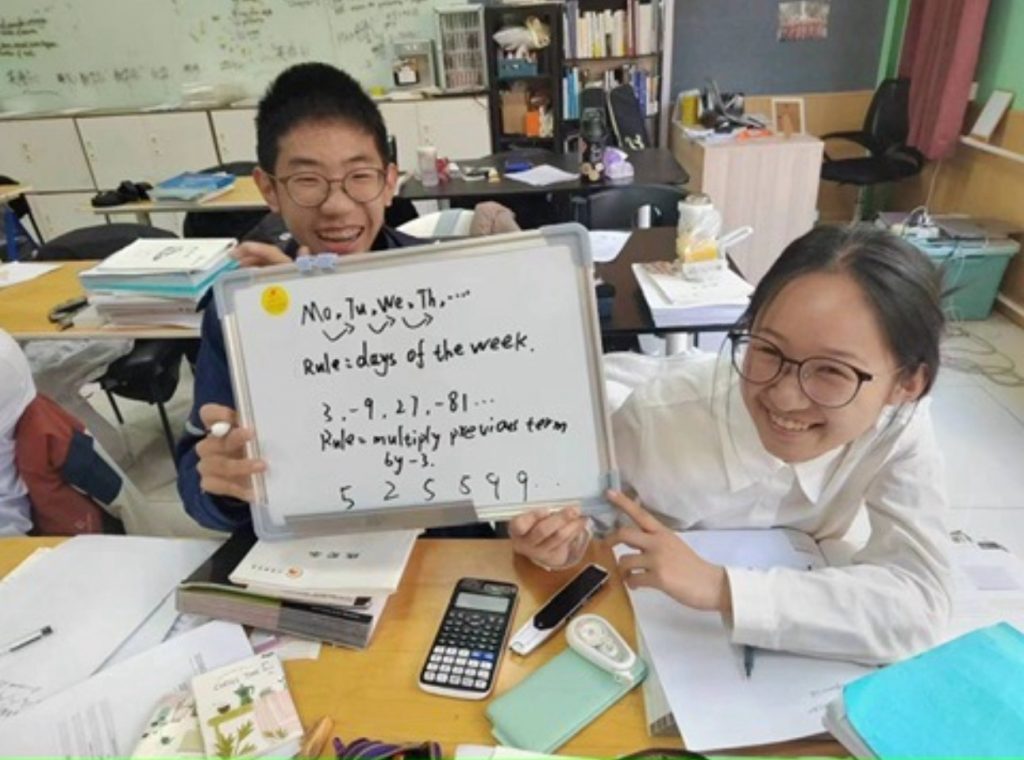

For children like us, the Spring Festival is undoubtedly the most anticipated season of the year, and because of this, they often start to calculate the distance from the New Year after the solar calendar, as if the Spring Festival is a distant and difficult place to reach. One of the reasons is that you will receive New Year money in the New Year, which was originally meant to suppress and exorcise evil spirits, but in fact, in our opinion, when we make a lot of money, when we see the elders, we will bow to the New Year, and our pockets will be full after Spring Festival. The second meaning is to take a step closer to growing up. One year older, the New Year represents a new round and growth. At the same time, the elders will take the descendants to worship their ancestors, so that the sleeping ancestors can also see our growth in the past year.

However, as I get older, I’m worried about another problem: it’s not far from the age of 18. Is it my turn to give New Year’s money to the younger generation? That’s really a big expense. Sure enough, tradition takes turns. When you grow up, you have to pass on the lucky money you received when you were a child. Last year, a lot of things happened, and I also began to gradually understand that the elders had a lot of emotions about the New Year, and it seemed that they had quite complicated emotions. After a year, the children, relatives and friends from other places will visit each other, and neighbours will visit each other to pay New Year’s greetings. It is a happy reunion. This is a joy. The clouds do not last all day long, and the shower does not end. The New Year’s departure is another spring rain that sweeps the elderly, and I often see the rain falling in the eyes of my grandparents. This is a sadness for me.

For us, the New Year symbolises the proximity to society and the maturity of the mind. Therefore, when I show the elders the harvest of this year, I can always hear the firecrackers ignite in their hearts, which is an unbearable joy and pride. However, this also reminds them of time flying by and their lives. The Chinese people’s words are implicit. The sentence “one year older” and the sigh inserted between the laughter hide all their helplessness, but they are happy in the present, and the world is at this time.

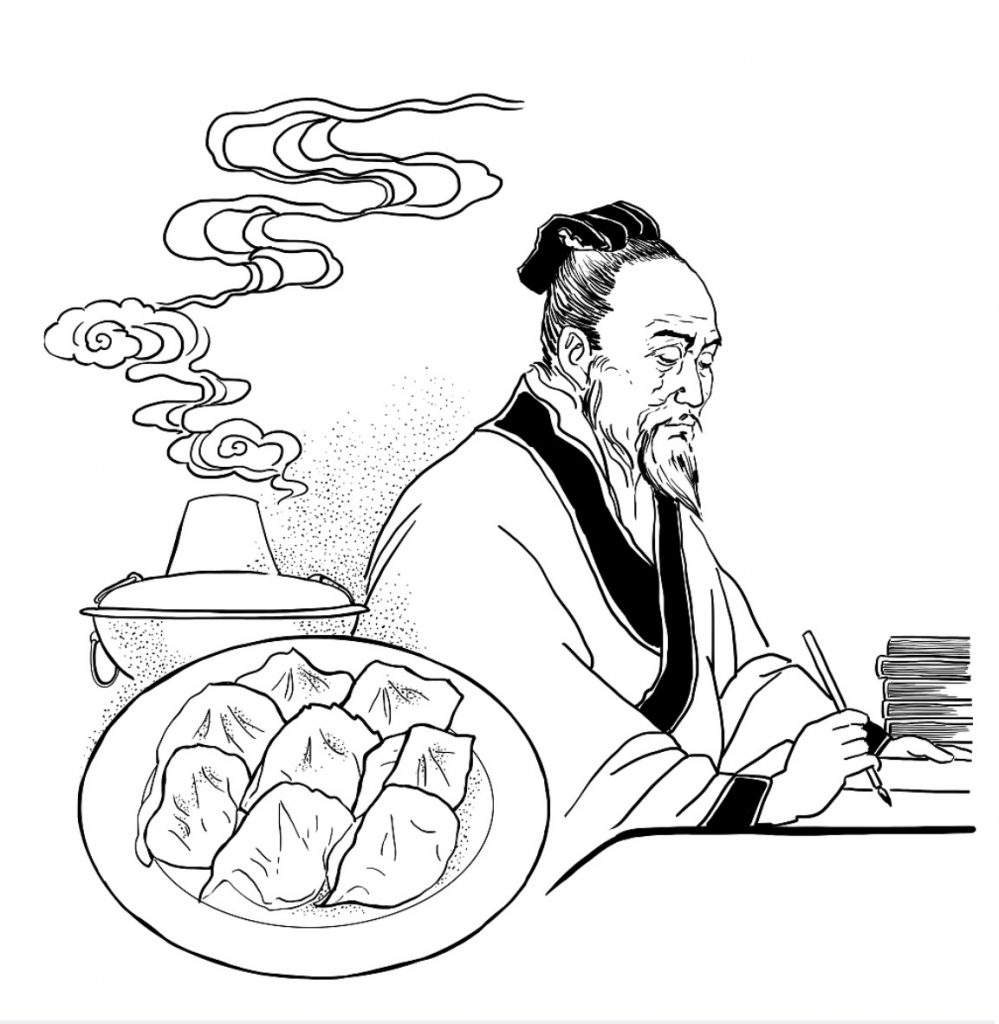

I lit the sky rocket firework inserted in the yard. With a sharp sound, it cut through the long night and knocked on New Year. After that, the fireworks and firecrackers were all on, and the night world was as bright as the day. It is not only entertainment for children, but also the custom of celebrating the New Year. Under the glow of fireworks, every family sits and eats dumplings made together, each with different flavours, which is the tone that people will recall in the future. It seems that there is a Spring Festival every year, 365 days or 366 days. We should cherish reunions more. Many things seem irrelevant at the time, but they become rooted in memory for a long time. For many years, they can seem to be dormant. When the memories wake up, they look at your hurried life and fell asleep slowly. But when I see them again one day, I see that time has worn out many so-called events in life, and they are firmly stuck there and have an incomparable weight.

When I realised this, I began to record my thoughts and I began to think about what life could create and leave behind. As the writer Shi Tiesheng said: “

“The process! Yes, the meaning of life is that you can create the beauty and brilliance of the process, and the value of life lies in the fact that you can calmly and excitedly appreciate the beauty and sadness of the process.”

Finally, sitting here at the dining table, I use my camera to leave behind this moment when we clink our glasses and celebrate this New Year of 2024.

(Original photographs by the author)