One of the benefits of working for a Chinese International Education company as I do is that compared to an ex-pat job for a British, American or Australian school in China, I get to access a lot more of China for direct experience of the country, the culture and the people. It’s true that I’m not paid the same salary as principals at some of the large western owned international schools in China, but personally speaking the opportunity for ‘close encounters with China’, more than makes up for this. The most recent of these school trips, we call them ‘study tours’, has been to the southern cities of Nanjing and Wúxī. Join me, and I’ll try to share with you local cultures and flavours.

Let’s start with a little geography and history to set the context. Nanjing and Wúxī are both in the eastern centre of China, close to Shanghai and in a province called Jiangsu. Nanjing is the capital of Jiangsu. A critical part of the geography is that both cities are located close to significant waterways, the Chángsānjiǎo as it’s called in Chinese, the three chief river corner, or in English, the Yangtze River Delta. Water transport was enormously important to the development of both cities as they grew by selling local products all over China.

This can be emphasised by the fact that Wúxī stands on the Grand Canal. The Grand Canal is one of the wonders of China. The Grand Canal ties northern and southern China together. A key to understanding Chinese history is the famous opening line of the fourteenth century classic novel ‘The Romance of the Three Kingdoms’ which starts ‘The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.’ Up until 1949 the history of China has been a story of fragmentation and unification. Running through this long history, the Grand Canal is like a knot tying south and north together, running from Hangzhou in the south to Beijing in the north.

The first sections of the canal were cut as early in history as 4th century BCE, and since then it has been added to, particularly in the sixth century (Sui dynasty) and the 13th century (Yuan dynasty). When I visited the Canal in Wúxī there was a constant flow of barge traffic, proving that the Grand Canal is a living waterway even in hyper-modern China.

Nánjīng means ‘south capital’, just as Běijīng means ‘north capital’. Nánjīng has been the most important city in China at many times in the past. In fact, twice during the period of Republican China, Nánjīng took on the role of capital city. One of the major patriotic sites in China is the Zhōngshānlíng, the Sun Yat Sen mausoleum and it’s located in Nánjīng, which was the leader’s chosen capital. I had the privilege of visiting the mausoleum. Sun Yat Sen was elected as the founding President of Republican China in December 1911. Sun died in 1925 and his body now rests in the mausoleum. Sun made a significant contribution to the modernisation of China before the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. In particular, he established three foundational principles – nationalism, democracy and social equality.

The Zhōngshānlíng

The architecture and layout of the mausoleum is a fittingly harmonious blend of Chinese and Western thinking. The mausoleum is built on the side of the Zhōngshān, the Purple Mountain and must be approached by climbing 392 steps, representing the 392 million Chinese people at that time. You enter the mausoleum area passing under an archway inscribed with the characters, 博爱坊, ‘Bo Ai Feng’ or simply ‘Universal Love’. Half way up the climb you come to the three arched marble gate. Over the central arch are words from Sun Yat Sen himself, ‘天下为公’, ‘tiānxià-wéigōng’ or ‘the whole world is collectively owned’. In the main mausoleum hall are three arches representing the three pillars of Sun Yat Sen’s political leadership – “Nationalism” (民族), “People’s Rights” (民权) and “People’s Livelihood” (民生). The mausoleum also features a striking statue of Sun Yat Sen himself.

It was fitting that I went with my Chinese students to show respect to such a change leader. Like them, he came from a humble background. We hope that like him, our students will use their international experiences and education to make their contribution to improvements to the country and the lives of its people.

tiānxià-wéigōng

There is another aspect of Nánjīng’s history that we must pay respect to. In 1937 the Chinese fought heroically to protect their then capital city from the invading Japanese Imperial Army. In a horrifying and shameful event, when soldiers from the Imperial Army entered the city they behaved appallingly, slaughtering and torturing the civilian population against all the international rules of war. There are sites you can visit to reflect on the full horror of the ‘Nánjīng Massacre’ as it is called.

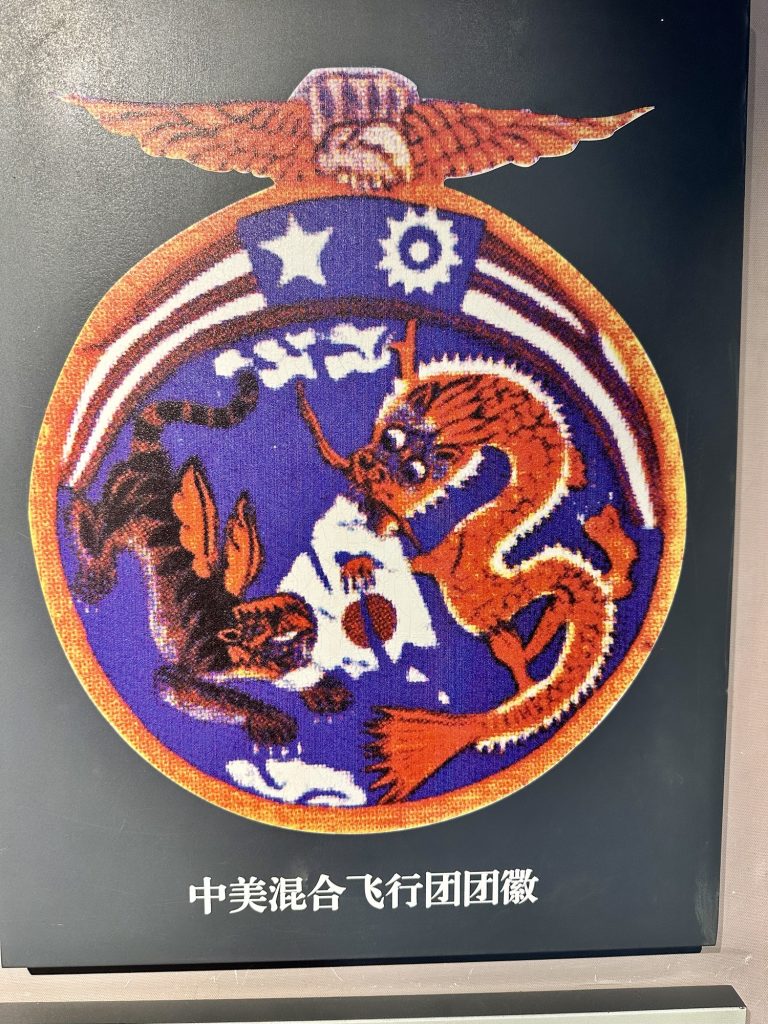

However we chose to remember this era in a different way. Also on the mountain is a very modern museum dedicated to the resistance to the Japanese armies at that time. In Chinese it’s called the ‘ Kàng Rì hángkōng lièshì jìniànguǎn’ or the ‘The Memorial Halls for the Pilot martyrs killed in the anti-Japanese resistance’. It is the final resting place of 170 pilots who lost their lives in the air battle above Nánjīng. We can think of it as the equivalent of the Battle of Britain fought to save the United Kingdom from invasion in 1940. Amazingly, just as the RAF in Britain was assisted by pilots from across the world, including nearly 200 from Poland and nearly 500 of Afro-Caribbean heritage, the skies above Nánjīng and south China were also defended by international forces opposed to fascism.

In particular this museum pays tribute to the sacrifices of American airmen who fought alongside Chinese comrades in arms as ‘the Flying Tigers’. This is a fascinating story that needs much more detail than I can give here. It took place in 1941 when the Japanese Imperial Army seemed certain to overrun China. Chinese forces remained in control of areas in the southwest around Chongqing and Yunnan. The Japanese forces were attempting to complete a pincer movement, moving up from what was then Burma and down from the north.

A volunteer force of pilots, mainly American, but with a few British, formed alongside Chinese aviation units to deny the Japanese the control of the skies that would have paved the way for their victory. The museum is full of fascinating and poignant exhibits, paying testament to the shared heroism of all who gave their lives to save China and her people at that awful hour. The visit was especially poignant for me because my grandfather on one side was an RAF pilot and my grandmother on the other side, was part of an artillery crew defending Southampton from bombing raids. I felt an enormous connection to the lives and sacrifices recorded in the museum.

Now let’s move on to Wúxī. Wúxī is part of an area that is sometimes called Jiāngnán, that is a geographical and cultural complex around the delta of the river that we call Yangtze in English. As you might imagine from its location, water plays a big part in the lives and culture of this area. It is in Jiāngnán that you can find the best examples of the phenomena of the ‘ water-town’. These are urban developments that took place entirely based around the networks of rivers and canals that flow everywhere through the delta.

In a water-town, houses nestle right up to the waterfront, often backing onto it directly. This was a reflection of the fact that the lives of water-town dwellers entirely revolved around the waterways. Research has shown that before the twentieth century, transport links in Jiāngnán were almost entirely by river or canal with very few roads. These towns prospered on trade carried up and down the watery arteries. Wúxī for example was the heart of a thriving brick and tile industry. From here, construction materials were carried all over China, bringing employment and wealth to local people. People washed their clothes from steps leading down to the river. People lived on diets of fish and fowl sourced from the waterways. Parallel to the rivers and canals were lanes crowded with businesses, busy buying and selling goods and products traded by boat.

And these water-towns are still engines of economic growth today! The new trade is in tourism. It probably wasn’t the intention of the original town designers, but the layout of these water-towns are perfect sites for visitors. Along the waterside itself are the picturesque buildings themselves. In Wúxī the Watertown area is called Huìshān. In Huìshān many of the water front houses have been whitewashed, making for harmony with the flowing water. At night the river area is filled with neon light which reflects in the waves and off of the white screens of the houses to create what is called ‘son et lumiere’ – a sound and light show, which looks intriguingly like the famous Van Gogh painting ‘Starry Night over the Rhone’.

Furthermore, these riverside houses and the surrounding lanes are perfect for the favourite Chinese pastime – snacking. We English have our abilities in this area-just think of the sandwiches, pasties, crisps and cakes that we fuel ourselves with. However if snacking was an Olympic event, the Chinese would certainly be in a medal position. The cobbled and charming streets that thread their way parallel to the waterfront are thronged end to end with an inescapable array of 小吃, xiǎochī, or ‘little bites’. There will be local delicacies, national favourites and of course now, an increasing number of international temptations, especially KFC. As I’ve remarked in other blogs, the Chinese people certainly share a sense of wanderlust with we Brits. Amazingly at its peak in 2019, internal travel and tourism earned the Chinese economy over 6.5 billion rmb, about 700 million pounds!

Let me share with you my favourite Wúxī savoury. I find something called ‘xiǎolóngtāngbāo’ irresistible. xiǎolóngtāngbāo are little parcels of paper thin pastry, containing a filling – meat, seafood or vegetable, which swims in its own little serving of delicious broth. Yummy! Wúxī has its own versions of these and I was able to enjoy them on the visit. The pastry skins are just as light and delicate as xiǎolóngtāngbāo across China, but the Wúxī speciality has a sweeter taste to the soup. The sugary broth makes an interesting contrast to the saltiness of the filling. However I should share with you that in my humble opinion these snacks taste even better with a tiny sprinkling of chilli sauce so that you have a blend of sweet, salt and spicy flavours in one.

Wúxī xiǎolóngtāngbāo

There is another shared love between the Chinese people and the British people that I’ve written about before – gardens! You cannot leave Wúxī without visiting at least one of the incredible courtyard gardens that bring green spaces to the town. So come with me now and we’ll visit Jichang garden, in Huìshān ancient town in Wúxī.

The design of this garden is very different from English ideas. English gardens usually create a single landscape so that from a vantage point you can see and appreciate the whole garden. There might be a variety of beds with different plant varieties, but the gardener will work towards an overall harmony that can be appreciated from different viewing points, usually strategically placed seats.

The Jichang garden is more like China herself, a complex of different environments, interconnected by a range of intriguing pathways. There is a lake environment, where a range of lush trees and trailing vegetation surround a lake, well stocked with plump fish. To move around, you cross aesthetically designed bridges that cast graceful reflections into the still waters. There is a mountain environment, where roughly hewn rocks have been assembled into narrow mountain passes, with streams cascading through the centre, forcing you to take precarious steps. There is a temple landscape, where the chiming bells and smoky incense of Buddhism harmonise with the complex roots of ancient trees and the mantra of bird song. Each environment is artfully arranged, to look as natural as possible.

You can’t help but wonder about the wealth and privilege of the family for whom this garden was originally built. Maybe like me, it will bring to mind the luxuries of the lives of the characters in ‘Hónglóu Mèng’, ‘The Dream of the Red Mansion’, the famous novel written by Cáo Xuěqín in the eighteenth century, describing the mansions and gardens of a wealthy family. And then another thought comes to your mind. Up until the modern China, this garden would have been out of the reach of nearly all of the Chinese people. And now it is the property of everyone, not a few. The garden walls have been broken down and anyone with a few rmb to pay the entrance ticket can enjoy the garden design and take whatever ideas it inspires in them back home with them after their visit.

Gardens like that at Jichang at Wúxī are a practical expression of Chinese poetry and philosophy, art made nature. The seed of it is planted in my mind. How wonderful it would be to have more Chinese style gardens like this in England.

If you haven’t done so already, I hope that one day you might have the chance to visit this beautiful corner of China and experience the Inspiration of connections to the UK yourself. Until then I hope that my article has shared something of the local flavours with you.

天下为公’, ‘tiānxià-wéigōng!

( all photos are originals by the author)