I’m sure you’ve all noticed that Dragon Boat festival has arrived. We can look forward to the spectacle of exciting and colourful dragon boat races across the globe!

Since 2008 this festival has been a public holiday in China. In 2009 it was added to the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity’. UNESCO states, ‘”Dragon Boat Festival strengthens bonds within families and establishes a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. It also encourages the expression of imagination and creativity, of contributing to a vivid sense of cultural identity.’ In this article, let’s see if we can get beyond the sporting images of dramatic races, to find some of the spirit of harmony at the festival’s source.

Let’s start with the name. If you know any Chinese at all, you’ll quickly see that the name ‘端午节 – duānwǔjié’ has nothing to to do with dragons, or even boats. It means, ‘the fifth day of the fifth month’. If you’ve been following my Chair’s Blogs, through the year, you will have noticed a theme. Every festival in China has ancient origins which tie it back into the changing seasons and the relationships between people and nature. I believe the same is true in England. Take away the Christian customs and you’ll find the old ‘pagan’ traditions linked to the land, the rivers and the skies.

So what was important about the fifth day of the fifth month? For the ancients, it was the time of two critical and linked events. The heartlands of China, the central areas around the great rivers, were very vulnerable to flooding. Flooding brought a series of threats to human life, including outbreaks of fatal diseases caused by waterborne insects and bacteria. Balanced against this was the fact that controlled flooding had the potential to significantly improve the fertility of farmlands and so the amount and quality of crops to feed the people.

In the days before technology, ordinary people had no way on earth to control any of these natural forces. There’s a Chinese idiom that expresses the puny powers of people in situations like this – ‘tángbì-dāngchē’ – like an insect trying to hold back a chariot. From this understanding it’s easy to see that rituals and traditions would be used as a way of trying to gain control, or at least, influence over these unpredictable events.

Enter the dragon! Since the very origins of Chinese culture, dragons have been associated with the strength and the power to control nature, especially the wind, the rain, rivers, lakes and seas. One of the nine types of dragon, the Lóngwáng, was able to control the wind and the rain. In fact if you think about it, there’s a powerful visual harmony between the long, winding, serpentine bodies of Chinese dragons and the shape of rivers. So at a time when the rivers were both a powerful threat and a powerful friend, what was more natural than putting a colourful, carved dragon head on the front of a boat and taking to the river to invoke protection from friendly local dragons.

Dragon boat racing is only one of a number of protective customs followed in order to ensure a harmony between people and their environment. Some of these are directly related to the medical threats to life caused by flooding. Maybe now they seem quaint and out of date, but their origins are very practical. One example is a type of alcohol called ‘xiónghuángjiǔ‘, made from Chinese cereals, but also containing traces of arsenic. The alcohol makes a powerful disinfectant and one past tradition was to sprinkle some of the wine in the corners of the house to cleanse it and keep away harmful insects. Another fascinating custom linked to this is to paint a protective character on the foreheads of children with a little of the spirit, again for protection. Don’t worry about the arsenic, in modern China ‘xiónghuángjiǔ’ has been replaced by plum wine!

xiónghuángjiǔ – Dragon Boat festival wine

Another example is the use of a herb which in Chinese is called ‘àihāo’. In English it can be called ‘mugwort’ or ‘artemesia’. As we know from ‘Harry Potter’, English culture used to be very rich in ‘herbology’, or the use of herbs for medical or magical practices. Mugwort is abundant in May and June. It’s leaves are very fragrant. During the festival it was the custom to hang bunches of the herb over doors and windows to keep away poisonous insects. Some would even make bracelets of the leaves and stems to wear to repel insects. As with many of these so-called superstitions, modern science has found that indeed mugwort does have medicinal properties which help with conditions of the liver or kidney. Mugwort leaves are antiseptic and can reduce fevers! They knew a thing or two, those ancients!

If you have followed my blogs, you will also know that numbers are frequently very important in Chinese festival thinking. As we’ve already seen the significant number for Dragon Boat is ‘five’. Alongside the ‘fifth day of the fifth month’, it was also considered that there were five poisonous pests, snakes, centipedes, scorpions, lizards and spiders. There are two traditional ways to protect people, especially vulnerable children against these dangers. The first is to paint pictures of these pests on red paper – of course red is always a lucky colour in China. Another is to make silk cut outs of the creatures. Then either the silk images or the paintings would be pinned on the wall, especially in bedrooms, in the belief that the pin or nail was impaling the insects themselves.

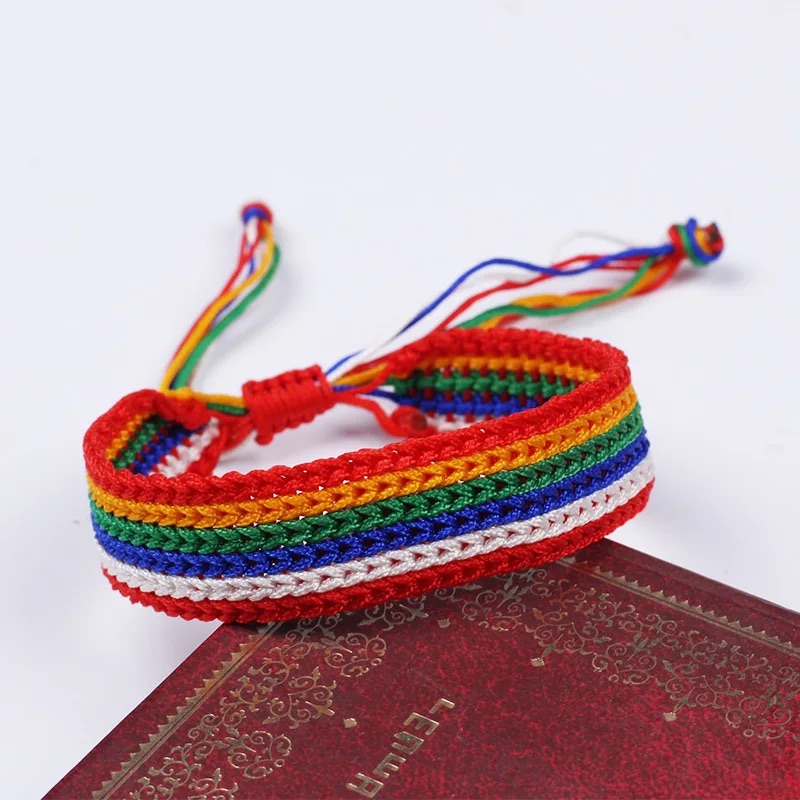

A linked custom is called the ‘five colour silk thread’. This was done specifically to look after children. Parents used to tie a five colour band of silk threads around the wrists of their child. The braids must be kept on until the first rainfall in summer when the pests were less frequent. And of course, the braid had to be thrown into a river, returning it to the source of protection. Intriguingly at around the same time of year there is a similar tradition in India called ‘Raksha bandhan’ which also involves tying protective bracelets around the wrist.

It’s easy for us to scoff at such superstitions but as anyone who’s slept in a room plagued by mosquitos will know, anything that restores your mental balance and helps you to get rest and sleep is to be welcomed. And we can only begin to imagine the terrible suffering of child mortalities in earlier times.

And here comes the part you’ve been waiting for – the food! Again, if you’ve been following my excursions through the alleyways of Chinese festivals throughout the year, you will know that every festival in China features a favourite foodstuff. In the case of ‘duānwǔjié’ we are talking about ‘zòngzi’. The heart of zòngzi is sticky rice which has been left to soak overnight and then cooked till it becomes a glutinous mass. The sticky rice is parcelled out onto bamboo leaves. A filling is then added. In South China the fillings tend to be sweet. In North China there is a preference for savoury fillings. The tricky bit is then to wrap the rice and filling into a neat pyramid shape, held together by the bamboo leaves and some cotton thread. Finally you will need to simmer your Zongzi for several hours until the filling is ready to eat. ‘Yummy!’ as Chinese people are fond of saying.

zòngzi

Which leaves one more duānwǔjié topic – the poetry! I know not everyone is a poetry fan so I thought I’d put this part conveniently at the bottom so you can choose to skip it. However there is a dramatic, even tragic poetry story connected to Dragon Boat. It happened in the period of Chinese history known as the Warring States – around 300 BCE. To put this in context, it’s the time the Celtic peoples were moving into Britain, the time of the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage, the time that Euclid was writing his famous books on geometry and that the ‘Ramayana’ was being composed in India.

Previously, central and northern China had been more or less united by the Zhou rulers. However as the power of the Zhou diminished, seven smaller states began fighting amongst themselves for hegemony. Our hero, Qū Yuán, was an advisor to the King of one of these warring states, Chu. He was also an accomplished poet. Unfortunately for Qū, he backed the wrong party in court and like many poets of ancient China, he was forced into exile. He turned his wanderings to good advantage, composing poems and learning about the customs and traditions of peoples living south of the Yangtze River. However, driven by a mixture of sadness about his endless exile and his bitter despair over the disasters besetting his country, he threw himself into the Mìluó River and drowned.

Qū Yuán has become part of the Dragon Boat festival. On the fifth day of the fifth month, local people are supposed to have begun a desperate search for his body in the river. They used local boats, similar to Dragon Boats, to look for his body. The villagers splashed the water with their boat paddles to frighten evil spirits away. They threw zòngzi into the waters so that the fish would eat the rice and other ingredients, instead of the poet’s body. Unfortunately Qū Yuán did not survive, but his remarkable poetry has. He was an extraordinary innovator who introduced new styles of writing and rhythms into Chinese poetry.

Qū Yuán, the poet of Dragon Boat

His most famous work is called 离骚 , Lísāo or ‘Parting Sorrow’. I’ll finish by introducing you to two remarkable parts of this poem. The first is its unique use of some the ideas of the ancient religions of China, which were a little like shamanism. On his travels Qū Yuán studied the herbal wisdom of communities he met on his way, leading to magical lines like these:

‘ I made a coat of lotus and water chestnut leaves

And gathered lotus petals to make myself a skirt

I will no longer care that no-one understands me

As long as I can keep the sweet fragrance of my mind.’

The second remarkable feature of ‘Lísāo’ is its humanism, especially its ability to face up to the full suffering of exile and yet still to try to find some inspiration. This gives insights into the mind of a poet who was later to end his own life from despair:

“ 路漫漫其脩遠兮,

lù mànmàn qí xiū yuǎn xī,

the road is boundless – cultivation so distant;

吾將上下而求索。

wú jiāng shàngxià ér qiúsuǒ.

I shall explore it from beginning to end.”

So, duānwǔjié, is about far more than dragon boats. As others have carried the sporting aspects of this event from China to the four corners of the world, let’s see what we can do to bring the deeper thoughts and harmonies of this festival to the world.

( all images courtesy of CGTN)