Double Eleven!

One of the most important events of the year for many Chinese people is taking place right now in November. It’s called Double Eleven and it’s the biggest shopping festival in the world. It’s a bit like Boxing Day and the January sales in the UK but on steroids. And curiously it takes place at almost the same time as the western shopping festival called ‘Black Friday’, which this year is on November 24th.

In this article I’ll share information about the Double Eleven phenomenon and some thoughts about what it means for the Chinese people.

What is Double Eleven?

Double 11 only came into existence in 2009. Really it would be better to describe it as a festival of e-commerce. The person behind Double 11 is Zhang Yong, the founder of an online retail giant called Tmall. He was looking for ways to boost the Tmall brand and hit on the idea of an on-line shopping event.

We need some background on Tmall. Tmall operates as an on-line platform for branded products, both domestic and international. By 2020 Tmall had grown to become the largest authorised mobile and online trading platform for brands and retailers in the world. We can understand Tmall as an online digital market place where retailers can set up an electronic market stall, without the costs of a physical infrastructure.

Double Eleven is not just about consumerism.

From an economic point of view Double Eleven is also about innovation. It offers a platform not only for new products but also for new services. E-commerce platforms encourage a whole economic eco-system of growth. Many of the businesses can be categorised as small or even micro enterprises. An important aspect of Double Eleven is the way it supports the development of finance, logistics, technology and even training for the skills of e-commerce.

I think it’s also important to understand the role of e-commerce for what in China is called ‘小康’, xiaokang, or making sure there is a level of moderate prosperity across the whole society, without ‘left behind’ areas of inequality. The on-line market places can be joined from anywhere in the country, bringing benefits to enterprises and consumers who live outside of the highly developed urban centres. A new platform called Pinduoduo, believes that every year it is seeing 167 per-cent growth in China’s much smaller fourth and fifth tier cities.

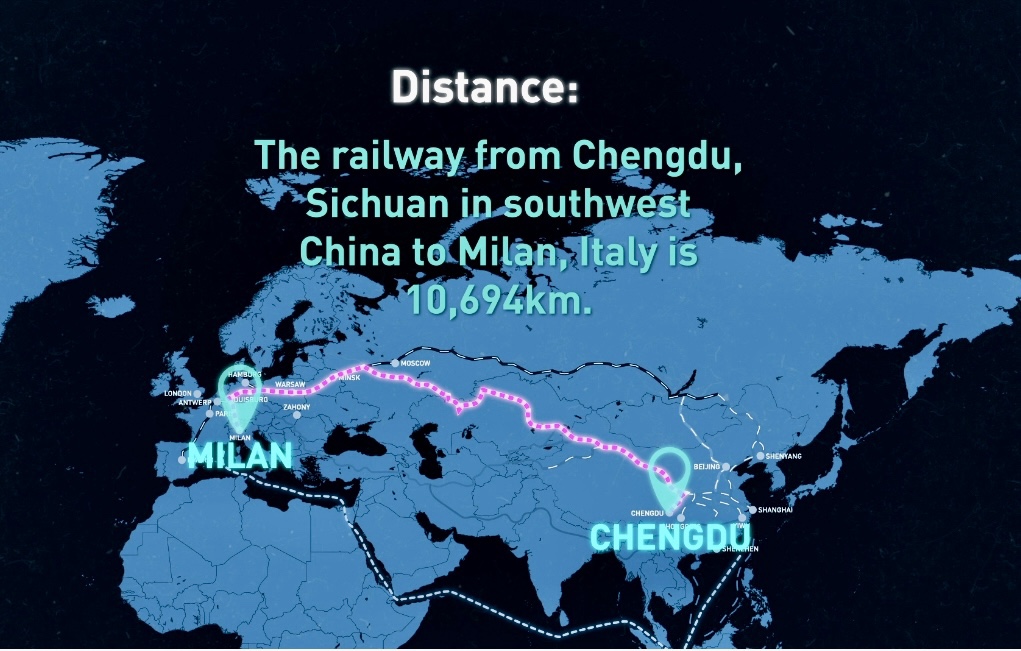

Seen in this way Double 11 begins to have cultural as well as economic significance. It is a critical part of opening up the Chinese economy to international producers. In 2022 Double 11 brought more than 2,600 overseas brands to the attention of Chinese consumers. Products and services were on sale from 79 countries and regions of the world. We should understand this in relation to the Belt and Road Initiative which is improving connectivity to China from across the world. Retailers from any part of the globe can now open doors to trade in China through the Double Eleven platform.

The phenomenon of Live-Streaming

The second cultural phenomenon that is markedly different from traditional patterns of shopping in the west is the emergence of live streaming. Again comparison with a physical market can be made. If you’ve ever been to a marketplace you will have had your attention caught by the show-woman or showman, attracting you not only by the quality of their wares, but the quality of their entertainment.

Live-streaming at Double Eleven is the commercial equivalent of the Olympic Games for the celebrities of this skill. In 2022 live-streamers generated more than 15 billion US dollars of sales. At the peak of the 2022 , 583,000 orders were being placed every second. Live-streaming brings opportunities for new entrepreneurs from across China, especially the still developing economies of the rural west and south-west. One of the most lucrative and valued corners of the live-streaming market is held by farmers and agricultural workers who can use the platform to sell organic produce and cultural products such as textiles directly to the doors of city dwellers.

Li Jiaqi, the live-streamer pictured above, sold so many products on line that he earned the nick-name ‘the lipstick king’. Then he notoriously risked his reputation and market share when he concluded an on-line argument with a customer by implying she was too lazy to earn the money to buy his products. The strength of on-line opinion in China can be seen in the fact that he has since apologised for his lack of values, “I should never forget where I come from and shouldn’t lose myself.” Social media in the West is not particularly known as an arena for public apologies.

Shopping and Culture

While we may have all kinds of reservations about consumerism, that shouldn’t blind us to the cultural importance of shopping. If we read Michael Woods’ ‘The Story of China’ he paints vivid pictures of places like 12th century Kaifeng where shopping was the engine of a renaissance of art, culture and life-styles. In his wonderful social history ‘Empire of Things’, Frank Trentmann (2017) opens with an account of shopping fashions from 1808 written by the Chinese poet Lin Sumen. Part of this different perspective is to shift the focus away from the seller to the buyer. As Trentmann puts it ‘it was the values these societies attached to things that set them apart’.

How to join the Double Eleven users community

My students are of course expert users of Double Eleven. They explained to me that a co-operative sub-culture has developed around the event. The volume of information about potential on-line bargains is simply far too much for any one person to manage. And so they work together almost like a team of hunters to guide each other to catch what they need.

They taught me two essential internet catch phrases for this activity. The first is ‘种草’ or ‘zhongcao’ which literally means ‘to plant grass’. However it is internet slang for recommending a bargain to a friend. I guess in English we’d say planting the seed of buying a product. And then there is its equally vivid opposite, which is ‘拔草’ or ‘bacao’ which means ‘to pull up weeds’. If someone tells you this then it’s a signal that you should avoid this product or seller.

Things like this go beyond linguistic ingenuity. The slang binds you into a group of knowledgeable consumers, clubbing together to make Double Eleven work on your terms.

It’s estimated that by 2025 the digital economy could be contributing 12 trillion dollars per year, which is 55% of China’s economy, so we’d be foolish to ignore its economic value. However we should also be wise to the ways in which Chinese citizens make use of shopping events like these to develop their own sense of value and community.

As one of my students said, ‘ Everyone will be immersed in pleasure on November 11th, that’s why the Chinese like this day very much, because a joyful day is what we need most. Double Eleven not only meets our material needs, but it also meets our spiritual needs, for Chinese, this cheerful day can also be seen as a festival, Double Eleven has taken root in our hearts!’