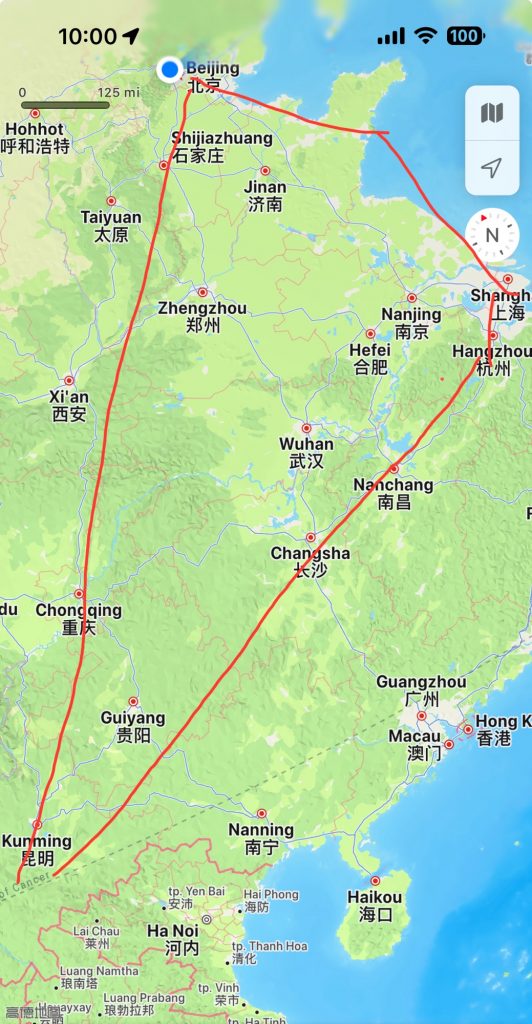

In the past three weeks I have taken advantage of the Spring Festival holiday period to travel extensively in China. Starting from Beijing I first of all travelled 2,087 kilometres to the city of Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province in south-west China. I then went on a further 350 kilometres to my first base, the city of Dali. Then another 300 kilometres south from Dali to the border city of Tengchong which is very close to the border with Myanmar.

After a return journey to Kunming I then cross-crossed central China, travelling to the city of Hangzhou, close to Shanghai and the capital city of Zhejiang Province. This is a further 2000 kilometres. From Hangzhou I climbed high into the mountains around the town of Lishui to a tiny village nestled in the mountain peaks called Songzhuangcun. The next leg of my journey was the 1000 kilometre trek northwards to Qingdao, a coastal city in the province of Shandong. Finally from Qingdao it was a simple matter of 650 kilometres back to Beijing.

Let me share with you some reflections from my journey.

If you’re thinking of any journey like this, I’d strongly suggest you travel by train. Cities across China are well connected by domestic flights and I could have halved my travel time by taking to the air. But you lose so much. Quite simply, your train window is a cinema on China. Or maybe more like an artist’s canvas with a constantly changing scenery of villages, towns, cities and nature. You journey between the familiar and the unknown. The flatlands between Shanghai and Qingdao remind you of the land reclaimed from the sea in East Anglia. The long dives through subterranean tunnels where the darkness is broken by sudden flashes of remote villages hung between precipitous valleys as you enter Yunnan is unlike anything you’ll experience in Britain.

The unfolding panorama is one reason for travelling by train. The second is the fact that train journeys connect you to not just the country but the people themselves. The longer your journey the more the chances of falling into conversation with fellow passengers. I find most Chinese people to be as reserved as us British, but if you have just enough Chinese to spark up a conversation you will be made welcome. From Beijing down to Kunming I was made to feel part of an extended family going home for the Festival. In Tengchong I improvised English lessons for curious 14 year olds who had never spoken to a foreigner before. From Shanghai to Qingdao a young entrepreneur entertained me with stories about his start up film business. Believe me, my Chinese is not good, but all Chinese people study English in school and a good number can hold a conversation in this second or even third language. How many of us could do the same in Chinese! There’s always a digital translation APP to fill in the gaps. And underneath it all is a friendliness and a tolerance that ease communication. In all those long kilometres of travel, at all times of the day and the night, there was not one unpleasant encounter.

Finally and perhaps most important, there’s the sheer efficiency and quality of China’s rail network. Of course it saves on the emissions caused by jet fuel. Currently approximately 30% of China’s electrical capacity is generated from renewables, with a target of 50% by 2025. I’m afraid to say Chinese trains are everything that currently British trains are not. They have excellent staffing with helpful conductors, regular in-travel cleaning and a catering service that regularly supplies snacks or even heated meals delivered to your seat. There’s even an APP now that allows you to book restaurant cooked food ahead in your next destination, which will be delivered to your carriage as you wait on the platform! Travelling in style! Furthermore the timekeeping of the high speed trains is legendary. My longest train journeys were all of approximately ten hours duration – and each trained cruised elegantly into its arrival destination at precisely the scheduled time.

Next I’d like to reflect on the diversity of travel experiences that China can offer a traveller, a diversity which often has its equivalents in Britain.

Encounters with history and culture are a given. For history, let’s take the ancient town of Heshun on the outskirts of the Yunnan city of Tengchong. The town is unaltered since the Ming and Qing dynasties, when it was an important centre for trade across south-east Asia. Walking in its narrow, cobbled streets delivers exactly the same feelings of nostalgia and connection with the past you get in a Cotswolds village in England.

For culture, let’s drop in on the New Year’s Day festivities at Songzhuangcun village, visiting a small temple perched on the mountainside. We all know that firecrackers and fireworks are a critical part of new year procedures to drive away bad luck. However in many cities lighting up firecrackers is banned, largely for environmental reasons. No such restrictions apply here and I’m thrust into the middle of the most enthusiastic and the most cacophonous ‘bàozhú’, firecracker display I have ever witnessed, where long lines of the little explosive devices are laid out along the mountain paths leading to the temple door. Soon the path is dripping red with debris and the air reeks of gunpowder and smoke. No chance of any evil spirits straying this way! And it would be exactly the same as dropping into some of the best bonfire nights for Guy Fawkes in England, the same high spirited, defiant revelry, fuelled by high octane pyrotechnics.

So far, so mainstream. But equally significant for me was the quirky, or even outright eccentric, characters I met along the way, showing different, unexpected faces of China. In Dali I stayed several nights in what we would recognise in England as an ‘alternative lifestyles centre’. Members of the ‘Veggie Ark, Future Space’ community in Dali are committed vegetarians, many of them vegans. Life in the community revolves around a communal kitchen where buffet meals are shared for the inspirational cost of £3:50. For even more dedicated vegans, meals entirely consisting of raw foods are available. The community has a programme of events focused around creativity and wellbeing. I meet a foreigner, from Switzerland, who had joined the community and teaches alternative therapies. It’s all very middle class. Guardian readers from the UK would feel very much at home here. The founder is called Wu Hongping. He’s an incredible character. He comes from a farming family. After travels abroad he returned to Dali, started growing food for himself and then realised that his home-grown, organic philosophies were increasing important to a materialist society. Now he is a farmer, a social entrepreneur and a wonderfully charismatic, inspirational teacher.

Another alternative lifestyle presents itself at Songzhuangcun, my homestay village in the Zhejiang mountains. If I said an ‘artist’s village’, or a ‘creative community’, you’d probably think of somewhere like St Ives in Cornwall, where art is a key part of vibrant cultural tourism. Come with me now to a remote mountain-top village, where Sun Yingying is striving to achieve the same magic. Songzhuangcun ought to be a dying village. Like so many other rural areas in China, it has been devastated by urbanisation. Yingying shakes her head and tells me there are no young people left at all in the village, they’ve all moved to Lishui, the nearest town in the valley or to nearby Hangzhou or Shanghai. Therefore there is no economic activity in the village. Indeed some of the beautiful mud-brick and wooden houses look shabby and forlorn. But Zhejiang Province has a hard won reputation as the leading area for rural revitalisation in China as the whole country strives to rebalance itself after decades of urbanisation and Yingying is making her own unique contribution.

I’ve seen wonderful village projects in my travels in the south-westerly provinces of Guizhou and Yunnan, but this one has a special beauty. Sun has worked with leading designers and local craftspeople to transform a number of retired properties into a stunning homestay accommodation. The project is called ‘Tao Ye’ – ‘Wild Peach’. The beautiful rooms are instant Instagram hits – or WeChat Wonders to give the Chinese equivalent. Tao Ye is successfully calling cultural and artistic travellers from across China and in future from across the world. But here’s the genius part. To kick start the creation of an ‘artist’s village’ Sun is developing the artistic and creative skills of the older people still resident in the village. She takes me to the art gallery in another restored abandoned local house to see their work. It has the wonder and authenticity of naive art. How much is from the artists and how much is from Sun herself is impossible to say, but their work is organic to the village environment. It might be the subject matter in paintings of the village itself, it might be the media, using raw, natural materials from the local environment or it might be the artists themselves, using their hands daubed in colour to create their designs.

Sun introduces me to one of her artists, a sprightly octogenarian called Ye Jin Juan. This woman should be the national symbol of rural revitalisation. When I meet her she’s setting up a demonstration of the rural craft of soy milk making for some visitors and will not stand still for one moment, except for a shy photograph. Sun tells me that Ye only left the village once in her life, for a short visit to nearby Wenzhou to see the sea, which apparently didn’t impress her much because she came straight back to village life. Her glowing, wrinkled skin and bird like twinkling eyes are witness to the wellbeing of mountain life. She drops her head humbly when I praise and encourage her art, but I can sense that developing these skills has given her a pride and meaningfulness in her life, revitalising her, alongside her village.

The trouble with travel is that we find it extraordinarily difficult to let things, people and places be as they are, just unfold naturally in front of you. We tend to two extremes of equally unhelpful reactions. On the one hand things can easily become uncontrollably ‘different’ and we condemn them as ‘strange’ or ‘foreign’. We see everything through the squinting eyes of anxiety. Or on the other hand we put on rose tinted spectacles and start to gush about how ‘wonderfully exotic’ everything is. Either way we are overlaying our travel experiences by projecting our own emotions, past experiences and prejudices. It’s easy to get China wrong. Even after ten years I know I sometimes do. That’s why I always try as hard as my limited communication skills will allow to tune in to local voices.

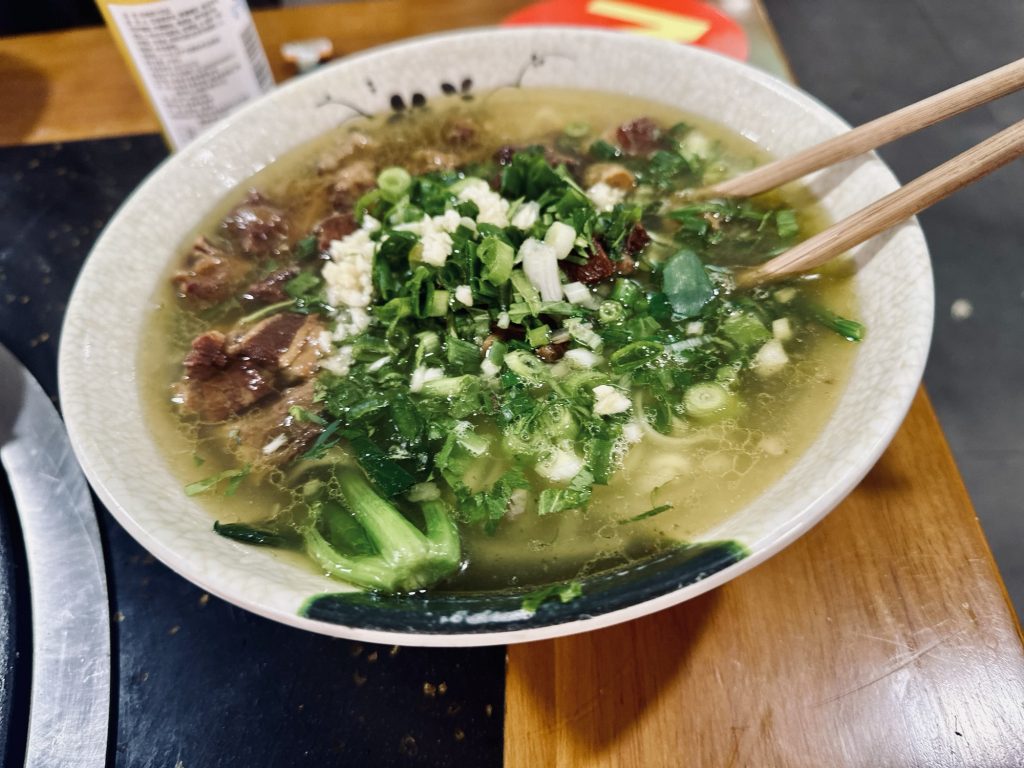

It’s like China’s vast and intriguing cuisine. You have to get out of the standardised, commercial restaurants to stand a chance of experiencing the local. Honestly, there will be things you can’t stomach. I love spicy food, but for me the third and highest level of spice in a Chongqing hotpot is forever beyond my range. Honestly, there will be times when you end up with a case of what the Chinese call ‘lā dùzi’, loose bowels. But only if you come to each meal with an open mind, and an open stomach, will you be able to appreciate the range of textures and flavours that compose the diverse symphonies of Chinese cuisine. And in time some of these will become your new taste of home. There’s a humble little roadside restaurant in Tengchong city, Yunnan where one taste of a bowl of rice noodles has all of the home comforts that a farm made pasty and locally brewed cider bring me in Dorset.

Bridges of understanding are waiting everywhere for you to explore .