13 JULY 2023 | Chris Nash

Throughout the summer and until October 8th there is an exhibition at The British Museum entitled ‘China’s Hidden Century’. It covers the period of the nineteenth century, which parallels the Victorian period in British history. And just as in Britain, this was a time of great turbulence and change. The challenge confronting this exhibition is how do you tell the story of social change through objects, the ‘things’ that museums inevitably have in their collection.

The exhibition starts with life at the late Qing court and glass cases of spectacular costumes worn by court officials and even by Empress Dowager Cixi who in effect ruled China from 1861 to 1908. Cixi is a controversial figure who even today divides opinion. To some Cixi is a negative presence, blamed for the failure of China to modernise. Supporters of this side of the argument point to evidence such as the way in which Cixi crushed the Hundred Days Reform initiative, an attempt led by Emperor Guangxu, to change the very way in which China was governed towards a more constitutional organisation. To others, Cixi is a brave woman doing her best in an impossible situation to balance competing, destructive forces and preserve the Qing vision of China. On this side of the argument, we have facts such as Cixi’s decision to support the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in its uprising against the Western powers then greedily and mercilessly trying to turn China into a colony, torn up and distributed amongst themselves.

My problem with this part of the exhibition is that it doesn’t really help us to understand the challenges that were influencing Cixi’s decision-making. Some in China still refer to this period as the ‘century of humiliation’ and in my opinion, the exhibition fails to witness the destructive ferocity with which Britain, France, Germany and Russia in their own ways tried to dismember China. One of the most notorious incidents from a Chinese perspective was the looting and pillaging of Beijing including the Summer Palace, the Yíhéyuán. Two cultural fragments stolen from the palace presumably by British soldiers, are presented in the exhibition. We have to ask, why haven’t they been returned to China?

But there was another side to this story of humiliation, a story of Chinese resistance. We know that China was at an enormous military disadvantage compared to the weapon power that had been developed in the centuries of warfare and imperial aggression in the West. This is represented in the exhibition by medieval-looking armour and equipment used by some parts of the Chinese military at the time. But this fails to tell the whole story. The fact is that at this time China was attempting to modernise, starting with developing the modern military technology needed to protect herself. In 1865 an arsenal was built in Nanjing by General Li Hongzang, who made sure that it produced artillery according to the latest scientific principles. In 1884 and 1885 there was a largely forgotten war in the west in which French armies attacked Chinese territory in northern Vietnam and Yunnan province. The reason it’s forgotten is that the Chinese successfully defended the borderlands and inflicted a number of defeats on the French army. France was at that time the second most powerful colonial power in the world, after Britain. In March 1885 a Chinese victory in the Battle of Zhenan Pass led to a crisis in France called The Tonkin Affair and the fall of the French government of the day. I saw elements of this history myself in a museum in Jianshui. Yet none of this can be found in the British Museum version of the ‘hidden century’.

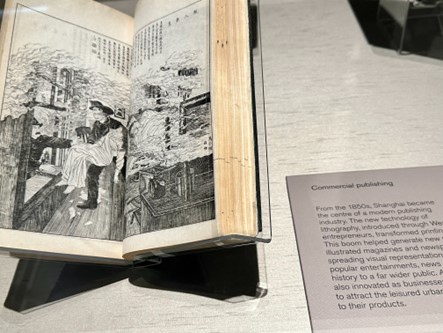

A section of the exhibition is concerned with Arts and Culture, which I know will be of interest to many SACU members. There is a fascinating story to be told here of the cultural impact of tensions between the traditional and the modern, between the 5000-year inheritance of Chinese expression and the increase in encounters with literary and other aesthetic ideas from the wider world. There are interesting examples of the beginnings of western influenced print media in Shanghai from the 1850s where, as would happen later with film, Chinese writers and publishers quickly adapted the lithographic medium to match the interests and needs of a Chinese audience. The exhibition does a good job of supporting the cultural contributions of women artists in the Qing era, for example, the talented painter Cao Zhenqiu, who was described as an ‘amateur, despite all of her splendid accomplishments, simply on the basis of her gender. However, I don’t think the exhibition gives us enough of a sense of the emerging Chinese modernism. From this period there is the story of the poet Huang Zunxian, who combined the ability to write in the Chinese classical style with a fascination with cosmopolitan content. Although he used traditional poetic forms as a literary method for making the complex changes of the period more understandable to both himself and his readers, Huang dismissed the typical content of earlier poetry as ‘empty talk’ and wrote instead about events from his travels, including America and Britain. In “Moved by Events” (“Gan shi”), a poem written to describe the court of Queen Victoria in England, where he was assistant to the Chinese ambassador to England he writes:

古今事變奇到此 The changes from past to present— they are so very strange indeed!

彼己不知寧毋恥 If we remain ignorant about them and us— would not it be a shame? Lines which could very well have been the subtitle to a deeper version of this whole exhibition.

This exhibition also tries to portray the everyday life of ordinary Chinese people at this time. This section opens with a dramatic glass case enclosing the rainwear of the working classes, all made from natural fibres. Ironically from our 21st-century ecological crisis, we should see value in such sustainable garments, but it painfully illustrates the fact that life in Qing China was the same backbreaking struggle as centuries of labouring ancestors. In my mind, the exhibition does not develop this theme enough. The rest of the exhibits in this section memorialise the material culture of an emerging middle class. Important as this is, it doesn’t do justice to events concerning the labouring and agricultural poor that would soon become the forces that set away Qing rule as China became a republic in 1912. I refer you to the relevant section of Michael Wood’s excellent ‘The Story of China’ to understand this period. According to sources he has found there were 285 peasant uprisings in 1910 as the economic and social fabric of Qing feudalism collapsed. Then he recounts the events of the 1910 Changsha Rising, which began when a young family, mother, father and two children, took their own lives in utter despair at inescapable poverty and starvation. Michael points out that the uprising and its brutal suppression by Qing forces were witnessed by 16-year-old Mao Zedong, who retold stories of the events in a famous 1936 interview with the American journalist, Edgar Snow. A year later, in October 1911 in the city of Hankow, all of these social and cultural pressures and tensions erupted in the Xinhai Revolution and the declaration of the new Republic of China on 1 January 1912. I would like to see these stories witnessed in the exhibition.

‘China’s Hidden Century’ represents the revolutionary spirit of the times in a different way. It chooses to focus on the incredible life of the poet and educator Qiu Jin. I’d urge all of you to follow the story of this remarkable woman. She called herself ‘鉴湖女侠; pinyin: Jiànhú Nǚxiá; or in English, ‘Woman Knight of Mirror Lake’. She could fight, ride horses and drink alcohol as well as any man. She left her husband and wrote a book of stories encouraging women to escape from family oppression. She co-edited a women’s journal called ‘China Women’s News’ (Zhongguo nü bao), which was so revolutionary it was shut down by the authorities. In 1907 she became the Principal of a school in the city of Datong, which under cover of being a sports college, prepared students for the revolutionary struggle. Her life had a tragic, heroic ending which I will leave you to find out for yourselves. Instead, I’ll choose to end on the ringing defiance of her poem, ‘Reflections’ :

- Lithograph publication from Shanghai

- Portrait photograph of Qiu Jin

- Court robe reputed to have been part of Dowager Empress Cixi’s