(Article developed from an original idea by Michael Crook)

At this time all over China people will be wishing each other not just ‘Happy New Year’, but also ‘龙 年 快乐‘ – ‘long nian kuai’le’ or ‘happy year of the dragon’. There are images of dragons everywhere in China at the moment. Which makes us stop and wonder – why are dragons such powerful symbols in both Chinese and British culture ? What are the differences and similarities between them?

It’s remarkable that the basic design of a dragon is the same across both cultures. A long snake like body, powerful claws, an impressive head with strong jaws and the ability to fly, although Chinese dragons don’t usually have wings. And it turns out the key design features of dragon like beasts are found in many cultures around the world, not just Britain and China. This leads me to conclude that there must be a shared ancestral memory of large powerful creatures that human beings had every reason to be scared of. Interestingly the origin story of Chinese New Year contains one such beast, a monster called Nian that likes nothing better than to devour a person or two on New Year’s Eve.

I think this common origin can be made even deeper if we look at further details. Both in China and the West, dragons are associated with the power of nature. In the West this association is with the Earth. Dragons live in lairs, dark, hidden caves under mountains. They represent Earth magic. In China dragons live under the seas or in the air. One of the oldest ideas about Chinese dragons is that they are bringers of rain, just about the most important factor in the lives of people in a country where up until 1975, three-quarters of the population were rural residents. Chinese dragons possess the power most vital to farmers – the ability to control the weather.

(image courtesy of CGTN)

In both cultures the tradition of dragons is very long. In the West we can find the origins of dragon like creatures in both ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. However the most immediate source of dragons is probably Ancient Greek mythology. Even the name has an Ancient Greek origin in the word ‘drakōns’. It was Ancient Greek thinking that first pushed western dragons in the direction of evil. Fighting a dragon became the challenge of choice of Greek heroes. This cultural inclination was reinforced by Christian thinking which linked dragons to the ‘serpent’ Satan. All of this mythologising led to the cultural high water mark for western dragons – the Middle Ages, represented by the myth of St. George.

Meanwhile over in China the earliest dragon depictions date from the Xinglongwa culture between 6200–5400 BC, while the Hongshan culture may have introduced the Chinese character for ‘dragon’ between 4700 to 2900 BC. The traditional image of the Chinese dragon appeared during the Shang (1766 to 1122 BC) and Zhou (1046 BC – 256 BC) dynasties.

In China the earlier idea of the dragon evolved into the ‘Dragon King of the Four Seas’. Each Dragon King is associated with a colour and a body of water, with the Azure Dragon or Blue-Green Dragon representing the east and the essence of spring, the Red Dragon the south and the essence of summer, the Black Dragon the north and the essence of winter, the White Dragon the west and the essence of autumn, and then there’s the yellow dragon, who is the incarnation of the Yellow Emperor.

So, the key difference in our tale of two dragons is that these symbols of power evolved in different directions west and east. In China, dragons became the symbols of the Emperors, representing the benevolence of their rule. Dragon emblems can be found in carvings on the stairs, walkways, furniture, and clothes of the imperial palace. It was against the law for common people to use things related to dragons in imperial times.

However throughout history dragons in China continued to be close to the lives of ordinary people. In rural communities, there was a dragon dance to induce the creature’s generosity in dispensing rain and a procession where a large figure of a dragon made from paper or cloth spread over a wooden frame was carried. Alternatively, small dragons were made of pottery or small banners were carried with a depiction of a dragon and written prayers asking for rain. The dancing processions had another handy purpose too, which was to ward off illnesses and disease, especially in times of epidemics. The dragon dance became a part of rural festivals and came to be closely associated with the Chinese New Year celebrations.

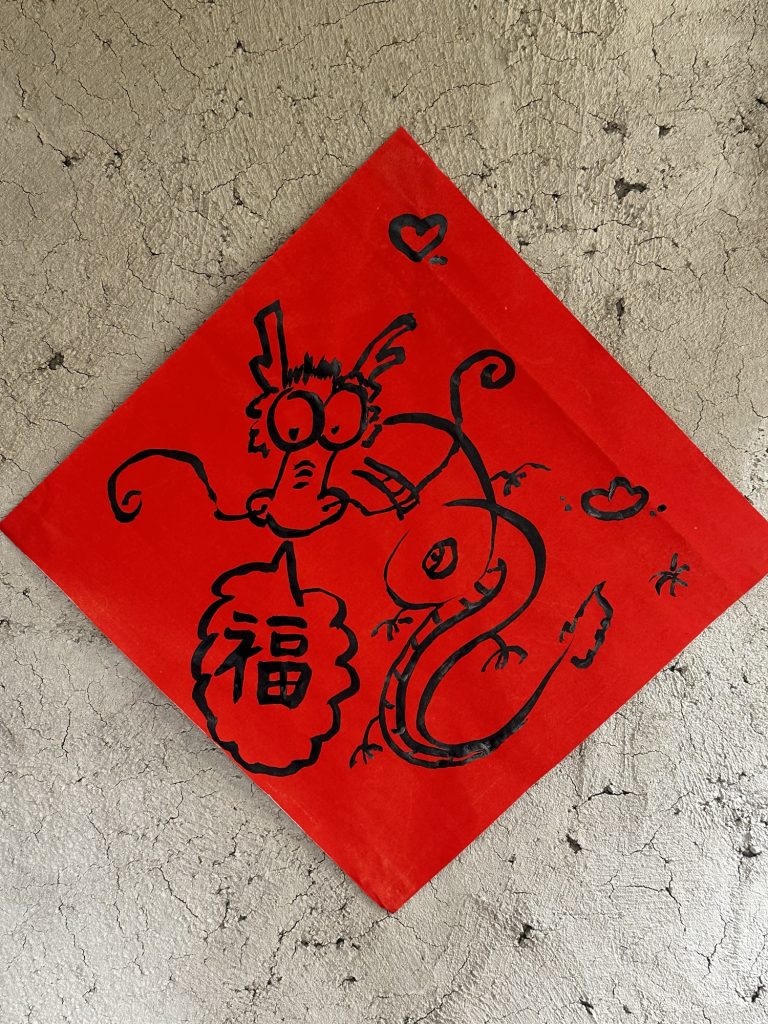

Which brings us back to today, the first day of the new year of the dragon. Chinese social media is overwhelmed by images of dragons. Many of them are cute and smiling, warm and friendly. Some are grander and more protective. Others glide magnificently and elegantly through animated gifs. Collectively they are an enormous expression of optimism about the year ahead. Of course we can dismiss it all as superstitious nonsense, but imagine for a moment the feeling of purpose that must come from even the possibility that your life and the life of your country for the year ahead is driven by such a creature, such a force for good.

(courtesy of weixin creator)

Before we end this tale of two dragons let me share two further thoughts.

Firstly although the mainstream image of dragons in the West is negative, there are elements of a more positive Chinese view here and there. One such can be found in the Celtic dragon tradition. Any Welsh SACU members will be quick to rally to the flag and point out that Wales is protected by ‘Y Ddraig Coch’, the red dragon that has roots in history back to the Welsh defeat of invading Anglo-Saxon armies in the mists of time. And closer to home for me, I’m very proud of the fact that my home-land of Wessex has traditionally had a golden dragon as its symbol. Indeed some historians believe that standards carrying designs with golden dragons were flown by the Anglo-Saxon army in the Battle of Hastings. Is it possible that magnificent and benevolent dragons are closer to original British culture than the snarling malevolence of the monsters from the Middle Ages ?

Y Ddraig Coch , the red dragon of Wales

Secondly, reflecting on the two evolutionary paths dragons have taken in the West and the East, could it be, as in so many areas, that actually this is a ‘yinyang’ of complimentary rather than opposing ideas. Dragons, east and west, present us with symbols of power. On one face we have images of what happens if power goes wrong and is used for evil. On the other face are reminders of how that same power can be used for good. A suitable point to pause for reflection as a new year opens for us all.

A dragon with the character 福, fu, meaning good fortune and happiness in the year ahead.

(All images belong to the author, unless otherwise accredited)