First of all let me send festive good wishes to us all.

I thought I’d try to bring some seasonal joy to this particular blog by celebrating the fun and merriment of live performance. I think this is particularly poignant since this is the first festive period since the end of COVID. I hope that all of you will enjoy the opportunity to cheer yourselves up by joining the audience of a show or performance.

At this time of year I always look back with a merry tear in my eye to the christmas shows in the school where I was Headteacher for many years. The students organised a show, the canteen staff cooked up a traditional christmas dinner with all of the trimmings and staff went out in their cars to chauffeur older members of our richly diverse community into school to join in joy. The evening always ended in a communal sing-song led by the school canteen staff, all local members of our community. We always managed to respect and celebrate diversity and at the same time come together in peaceful harmony. And live performance was the elixir which made this alchemy possible. The power of laughter and song to dissolve differences can be that magical.

I was reminded of this chemistry by a recent event I joined in Chengdu. I was part of the audience for a traditional Sichuan Opera, Chuanju. I’ve been to both Beijing and Shanghai Opera performances in the past and to be honest found them a taste quite difficult to acquire. I guess it’s that thing where you’re passionately interested in a culture or a cultural event, but still feel like an outsider, looking in, not quite sure what to make of it, despite all of the careful research you’ve done.

I needn’t have worried, this time I became an insider in a way I never expected.

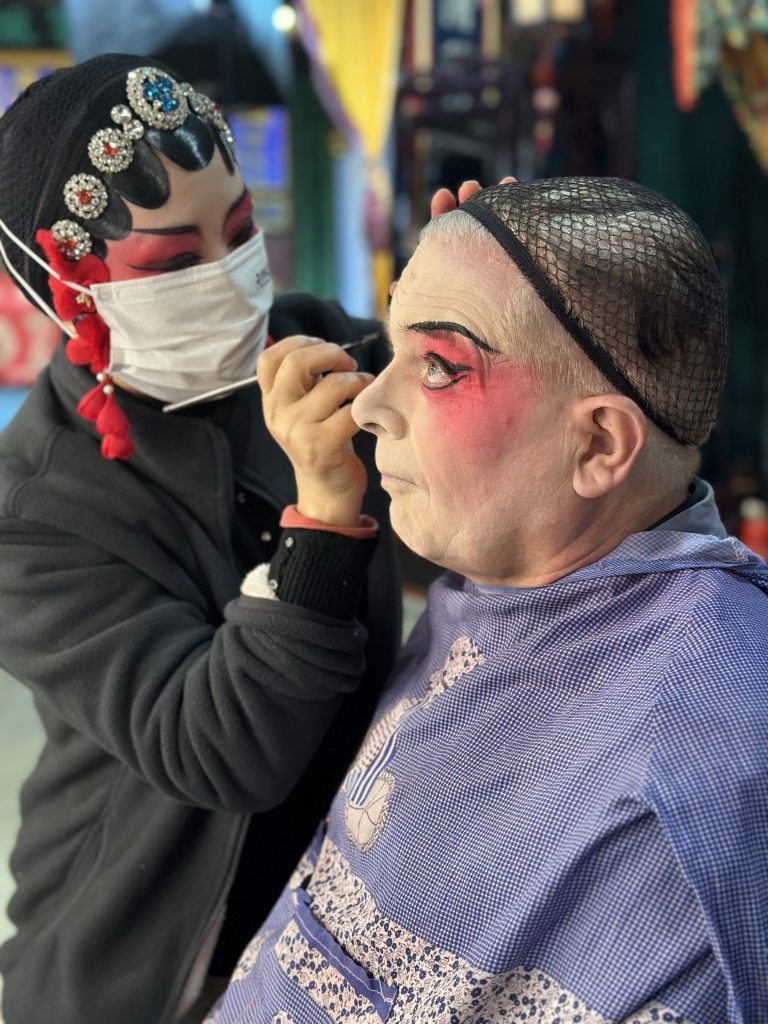

We had only just taken our seats in the large, beautifully decorated auditorium, when someone I could only assume was theatre staff beckoned me to follow her. Was I sitting in the wrong place? Had I broken a centuries old etiquette? A colleague came with me as a translator and we followed her, not to the exit, but to the area where the performers were getting into make-up. I’m sure you’ve all seen photographs of Chinese opera characters and know that part of the magic of the show is the elaborate make-up and colourful costumes. Maybe you’ve seen ‘Farewell My Concubine’, the Chen Kaige film set in a Beijing Opera House. Can you guess what happened next? Believe it or not I was offered the chance to be made over as an opera character and to go into costume. For this once in a lifetime opportunity there was a minimal charge. I invited any interested teachers and students to join the experience.

We talk in English about ‘the smell of the grease paint’ to express the sense of excitement and anticipation amongst the performers about to go on stage. I did have to ask, ‘You’re not going to put me on stage are you?’ but even after I’d been assured that we ‘extras’ would gather on a private stage, not the public stage, I felt totally a part of the whirl of preparations around me. A rainbow of masks were being carefully painted across the faces of the performers around me. All around the walls were wardrobe rails emblazoned with the myriad of character costumes. One by one the costumes floated down from the rack and transformed the caterpillar actors and actresses into dazzling stage butterflies. And in the mirror I watched myself transitioning too.

When my transformation was complete I was shown to the small private stage. By complete fortune my character was paired with that of one of my students. We went on stage together and we were walked though the basics of a scene. We were shown the poses to assume. We were shown the expressions needed to tell the story of the scene. I was presented with a fan and shown precisely the finger-grip and angles at which to hold it. Everyone around me was incredibly patient and kind.

It was all over in about ten minutes, but within that short time I had the wonderful feeling of being an insider in the traditions and artistry of ‘chuanju’, like an apprentice who has a glimpse of the creativity she or he aspires to. And I felt echoes of what performers in every culture and every age must feel, the goose-pimples of taking on another identity. For that short time I was neither foreigner, nor Chinese, I was the magnificent Wensheng!

Sadly I had to remove my gowns before re-joining the audience, but I was allowed to keep my make-up which drew astonished exclamations of appreciation from audience members and students alike. I wasn’t quite an opera star, but I had a flicker of insight into their stage-lit world. The show itself was a magnificent melange of styles and emotions. It was a variety performance to show-case the talents of Chengdu’s finest, not dissimilar to Victorian music-hall.

There were poignant and passionate musical interludes. There was a shadow puppet show which is such a deep thread in Chinese tradition it is inscribed in the Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. There was a breathtaking show of acrobatics and tumbling, cleverly constructed around an episode from the ‘Journey West’, the Xiyouji, better known as the story of Monkey King. There was a satirical comedy played out between an all powerful wife and a Chaplin-esque woeful but endearing husband which was delivered in pure Sichuan dialect, but hilariously punctuated with comic attempts to use English.

The excitement and wonder of the show all built towards the spectacular ending, which is a performance totally unique to Sichuan called ‘changing faces’. The performers flow across the stage in entrancing movements, wearing colourful, decorated masks. Magically, mysteriously, often mid-flight, one mask disappears to be instantly replaced by another. Each actor might change 5 or 6 faces. As the face changing proceeds, fans are introduced and the performers start to play with the audience anticipations in a delirious ‘will he, won’t he’ display of breathtakingly invisible illusions.

It seems to me that this sense of play and performance is deep in the heart of English and Chinese civilisations. Perhaps its something to do with the theatricality of both languages that have such tremendous range and depth. Perhaps there is an innocence in both cultures that can readily accept the wonder and enchantment of storytelling, what academics call ‘the suspension of disbelief’. If you’re looking for a modern example you need look no further than an audience of young Chinese faces under the spell of Harry Potter, every bit as bewitched as their British peers.

As one year closes and a new year beckons, let’s cherish what is both unique and shared in the diverse eco-system of cultural traditions between China and Britain and continue our noble work to share this understanding with wider and wider audiences.

I wish you all the joy of the festivities and beyond into the new year!

(All of the photos are originals taken by the author)