For the last week I have travelled with Grade 9 and Grade 10 students from my school in the city of Chengdu, which is the capital of the south-westerly province of Sichuan. You’ll be familiar with the name from countless restaurants in England claiming to serve ‘Szechuan’ dishes. It is not my job to act as an advertising agent for ‘Travel China’ so I’ll get the publicity out of the way immediately. If you have the chance to visit this fascinating location, please do so!

In this blog we are in the business of building bridges of understanding between the people of China and the people of Britain, so let’s explore links and connections between Chengdu and England.

Du Fu Caotang

First the poetry! Thanks to the tireless and inspiring work of our SACU President, Michael Wood, the great poet 杜甫, Du Fu, is getting better known to English language readers. Du Fu lived in the Tang Dynasty era from 712 to 770, but he is a living presence in Chinese culture today. I first came across his poems being recited and discussed by my students. One of the key characteristics of Du Fu’s work is that he is a ‘poet of exile’ whose art was refined by years of living as a misplaced refugee during the time that the violence of the An Lushan rebellion (755-763) destroyed the peace of the Tang and effected the lives of Chinese people at all levels of society.

In his excellent new book, ‘In the Footsteps of Du Fu’, Micheal expertly locates Du Fu’s writing in place and time, following his wanderings in central and southern China. How excited and humbled I was as I rolled south on the luxury of the modern high speed G308 train from Beijing to Chengdu, to follow almost page by page, the poet’s journeys, experiences and their expression in poetry.

In Chengdu the students and I visited 杜甫草堂, Du Fu Caotang, a park and museum dedicated to the poet, in an area where Du Fu built a cottage in 760 and found (temporary) sanctuary from the war. Michael Wood’s chapter on this is particularly memorable because he emphasises that many Chinese people, and not just the ‘intellectual elite’ still feel a living connection to the poet and his works. My version of this was to organise a bilingual reading of two of the poems, enthusiastically supported in Chinese by one of my students, at two particularly evocative locations in the park. Not only were there no disapproving or cynical looks, but even a small and appreciative gathering of Chinese visitors who politely applauded at the end of our improvisation. I hope the poet himself would have approved. As to the beauty of the surroundings, if I were the spirit of Du Fu you would find me there every balmy dusk evening, drinking a tea and performing my verses for anyone with the time to listen.

Personally I think to talk of Du Fu as the ‘Chinese Shakespeare’ or the ‘Chinese Dante’ is irrelevant and even patronising. Du Fu deserves to be recognised as a profound poet of the human condition on terms at once Chinese and universal. It is scandalous that his poetry is not more widely appreciated in western schools and universities.

Sanxingdui

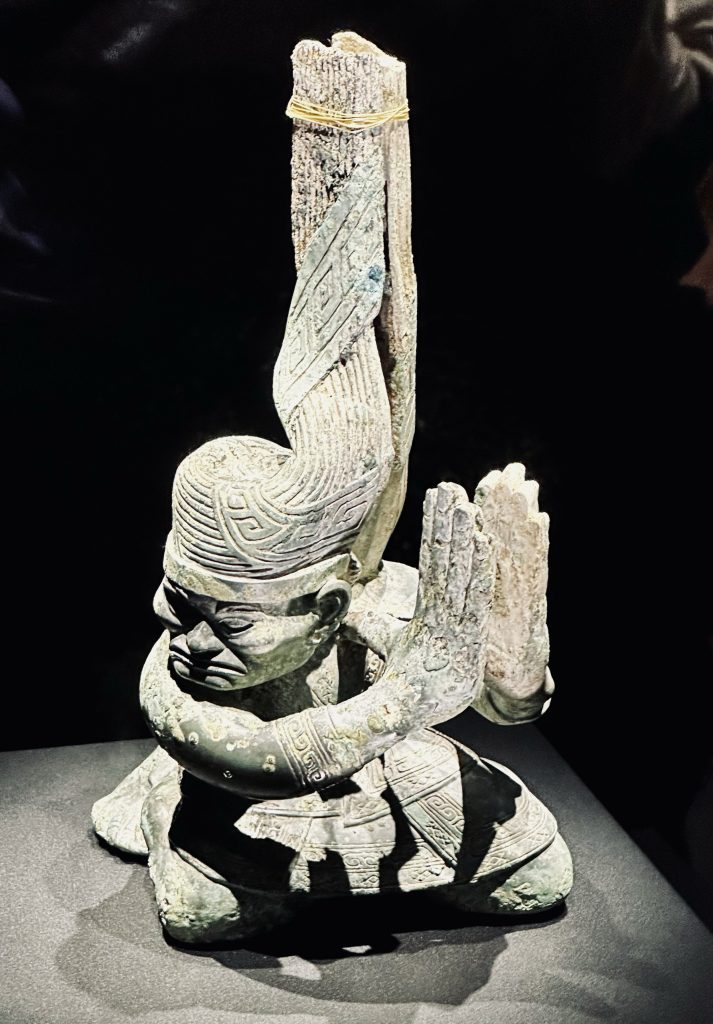

The second connection concerns history. Chengdu is home to one of the most fascinating Bronze age cultures in the world – the Sanxingdui, which flourished in this area in the eleventh and twelfth century BCE. This year an amazing modern museum opened on the site of the Sanxingdui excavations, a museum whose own beautiful design seems to have been inspired by the artistry and ingenuity of the Bronze Age ancestors. The museum is expertly curated with audio tours and signage in English throughout. The range of artefacts on display is spectacular, displaying an artistry capable of creations from minute but detailed bronze animals to a soaring nearly 4 metre tall ‘holy tree’.

Two thoughts struck me as I wandered and wondered, both with an international dimension. The first was how much of the creativity here was inspired by connections to the natural world. Animal forms are everywhere, birds, snakes, buffalo and tigers, sometimes twisting together with human bodies. Anyone familiar with Bronze Age art from across the world will recognise a similar motif, perhaps born from a renewed fascination with nature as city lifestyles replaced older agricultural modes of thought.

The second is the way that the malleability of metals such as bronze and gold seemed to fire the imaginations of a generation of smiths across the Bronze Age globe. Exhibits such as the ‘Standing figure holding a dragon shaped sceptre’ or ‘Figure riding a beast with a Zun on top’ (‘zun’ is a religious vessel) are Dali-esque in their imaginings. In the Aegean, in the near-East and closer to home in the expression of British Bronze Age metal-workers we can find similar inspirations from the liquid flow of molten metal into the solid forms of a mould. There are masks of fine beaten gold which seem to connect directly to the gold work of the mask-makers of Mycenae.

Just like the artistry of Du Fu the diverse faces of Sanxingdui culture should be more widely recognised.

Pandas!

No article about Chengdu can be complete without pandas. Panda pictures, panda fashions and panda accessories are inescapable everywhere in Chengdu because it is the site of the China Panda Research and Conservation Centre. I approached the visit with some trepidation because I’ve had a visceral hatred of zoos ever since reading Ted Hughes’ fierce poem ‘Jaguar’ at school. I needn’t have worried. Pandas are natives of the dense wooded forests in the bowl of mountains surrounding Sichuan. In particular they need bamboo because 90–98 percent of the panda’s diet consists of the leaves, shoots, and stems of this grass. And that is exactly what the conservation centre consists of, a landscaped bamboo forest threaded with the paths that city dwelling humans need to move around. In fact so successful is the natural environment that the notoriously shy pandas are quite difficult to see, often nothing more than a glimpse of black and white fur bobbing up and down, munching contentedly behind dense leafy screens.

Furthermore this place acts as a highly effective scientific research centre, funds boosted by the flocks of adoring panda fans and has produced scientific findings on topics as diverse as panda ecology, management, nutrition, behaviour, breeding, disease and heredity. The research has benefitted not just pandas but success in preserving the rich bio-diversity of the whole area.

And here is another connection from Sichuan to the world. It is one of the top 25 most biodiverse areas on Earth, with more than 10,000 alpine plant species and 1,200 vertebrate species. It’s no exaggeration to say that the work of places like the Panda Research Centre to conserve this local biodiversity is of critical importance to us all.

The Spice of Life

And so to food. It’s humbling to think that while the panda survives all its life on just one source of nutrition, we humans have developed culinary systems with a dazzling array of flavours, textures and ingredients. The sales pitch of popularised ‘Szechuan’ dishes in the west is that they are ‘spicy’. There’s a toehold of truth in that, but it doesn’t do credit to the range of flavours that constitute the spice. To start with there’s not a single Sichuan spice, but combinations of fennel, pepper, aniseed, cinnamon, clove, chilli and Sichuan pepper. Broad bean chili paste called ‘dòubànjiàng’, shallots, ginger and garlic are also commonly used.

The spice is complemented by the quality, freshness and range of ingredients used. Due to its climate, crops and livestock range from those of subtropical climates to those of a cool temperate zone. One of the best ways to appreciate this is through the culinary phenomenon that is Sichuan ‘huo guo’ or hotpot. Reduced to its essentials the hot pot experience consists of a shared bowl of broth where diners collectively boil and consume a range of fresh ingredients. It’s common for the broth pot to have two sections – one non-spicy, often mushroom based and the other fiery crimson with spice, including the humble but mouth numbing ‘málà’ peppercorns that are absolutely characteristic of Sichuan cuisine.

Hot pot is healthy and nutritious because the ingredients are all boiled there and then, preserving their vitamin content. There’s a rich range of oils to flavour the foods you fish out of the pot, but those are to your own taste. And above all it’s a wonderfully communal experience, unlike any western dining that I know. One of my favourite Chinese phrases is ‘xiāngpēnpēn’ which very approximately can be used to describe a rich confection of food flavours and fragrances and I defy anyone to eat hotpot without being drawn in to an equally ‘xiāngpēnpēn’ conversation.

Which allows me to conclude with a person to person anecdote. Most of the ingredients for hot pot are easily available in Chinese supermarkets in England, including the broth bases. You can also buy electric versions of the hot pots themselves. In summers in England, in bbq season, I would set up my hot pot in the garden on a table outdoors with the prepared ingredients ranged around it. It wasn’t long before the ‘xiāngpēnpēn’ drifted up over the garden fences. Nor was it long before the fascinated faces of my neighbours would pop up over the fence tops, noses twitching. And so I had bowls prepared to pass to them over the fencing, for our own English back garden version of the Sichuan communal dining experience. A little corner of north London that is forever Chengdu!

Let’s finish with a few lines from Du Fu, describing his Chengdu home:

“ I’ve chosen

this quiet woods and river bank

outside the city, well away

from business, dust, entanglements

here where clear water,

rinses away a traveller’s sadness.”

‘Siting a House’ ~ trans David Young, 2008.