One of the key things that drives me in my work for SACU is the knowledge that there is so much the people of China and the people of Britain could benefit from if we had genuine opportunities to learn from each other.

I was reminded of this recently. One of my former students now studying Urban Design in a UK university sent me her essay about Environmental Impact Assessments – which are legal mechanisms used in the UK to protect vulnerable environments. And there in one amazing paragraph she was paralleling and comparing an annual report into Teeside Incinerators and the Yangtze River Three Gorges project and thinking her way through both of these to next step improvements in the EIA process in both countries and globally.

So in this blog, let’s explore a little more the potential benefits for both peoples that might happen if educators from both cultures sat down and shared educational thinking. We can start with the legendary excellence of Chinese students in Mathematics. And it really is legendary. In the UK out of all A Level entries only 1.8% are for Further Mathematics, the gold standard of global mathematics. In my school alone at least half of the cohort will study this demanding A Level and no grade has slipped below B so far.

Let’s first of all entirely dismiss any ‘genetic’ explanations. There is no Maths gene. There are however lessons to be learned in two crucial areas. The first is the quality of Chinese mathematics teaching. Indeed the British government recognised this in 2014 when it organised something called the ‘Shanghai-England Maths Exchange’ enabling Shanghai teachers to deliver training and model their teaching methods in the UK and enabling English teachers to experience Shanghai Maths first hand. The benefits of this simple ‘people to people’ project were transformative. One of the English teacher participants , Afshah Deen, said,

“Seeing maths teaching in Shanghai and observing how lessons are planned and then discussed and refined by teachers there has been the most interesting and rewarding professional experience of my career. I’ve literally questioned everything I’ve done for the last eight years of teaching. It’s really inspired me to be a better maths teacher.”

The second strength that I believe the UK education system could learn from Mathematics in China is around ‘cultural capital’. This is the idea that when individuals are learning in the classroom they will be influenced by a myriad of thoughts and feelings formed from multiple encounters with the cultural eco-system they grew up in. And it’s the simplest little things in this cultural eco-system that make a difference. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has spoken of an anti Maths culture in the UK. This is made up of hundreds of jokes, instagrams and playground banter where Maths will be ‘dissed’ and dismissed. The limit of the Prime Minister’s thinking is to believe that you can solve this problem by simply introducing more of the same, without challenging the cultural assumptions.

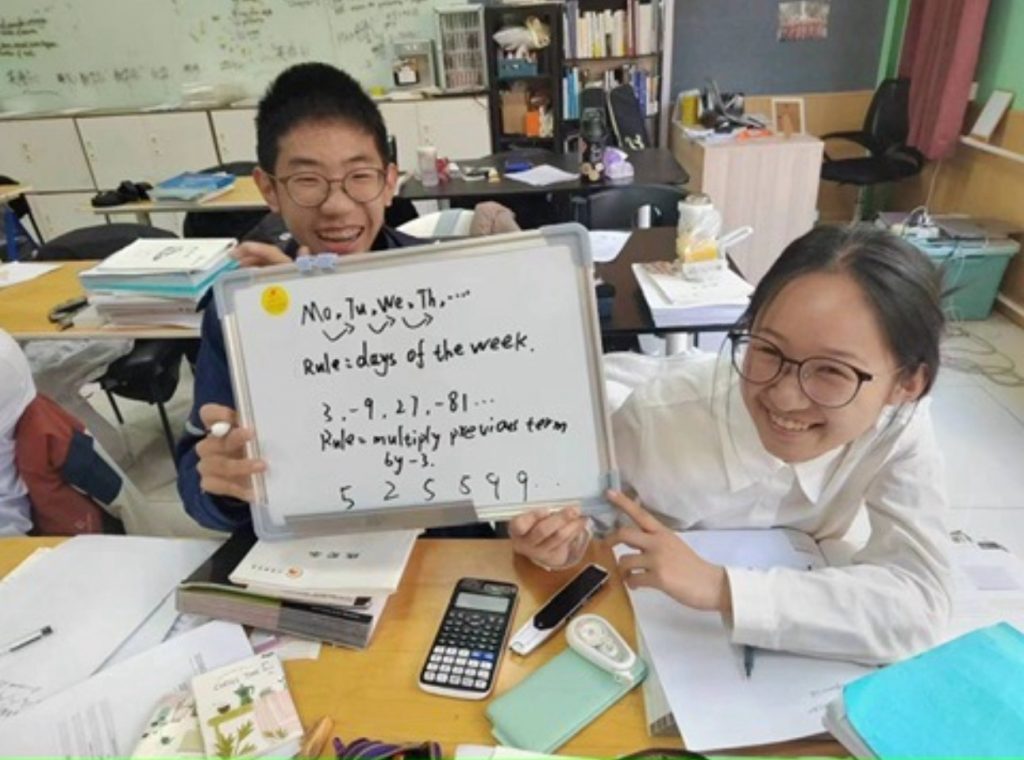

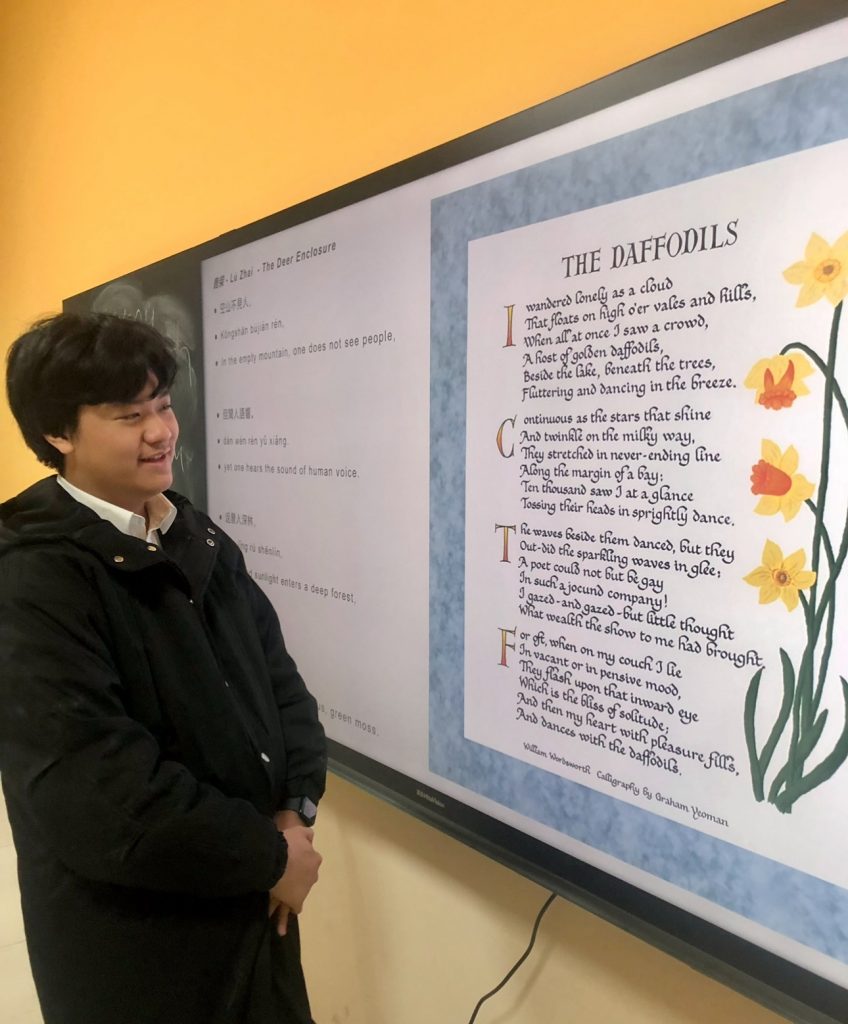

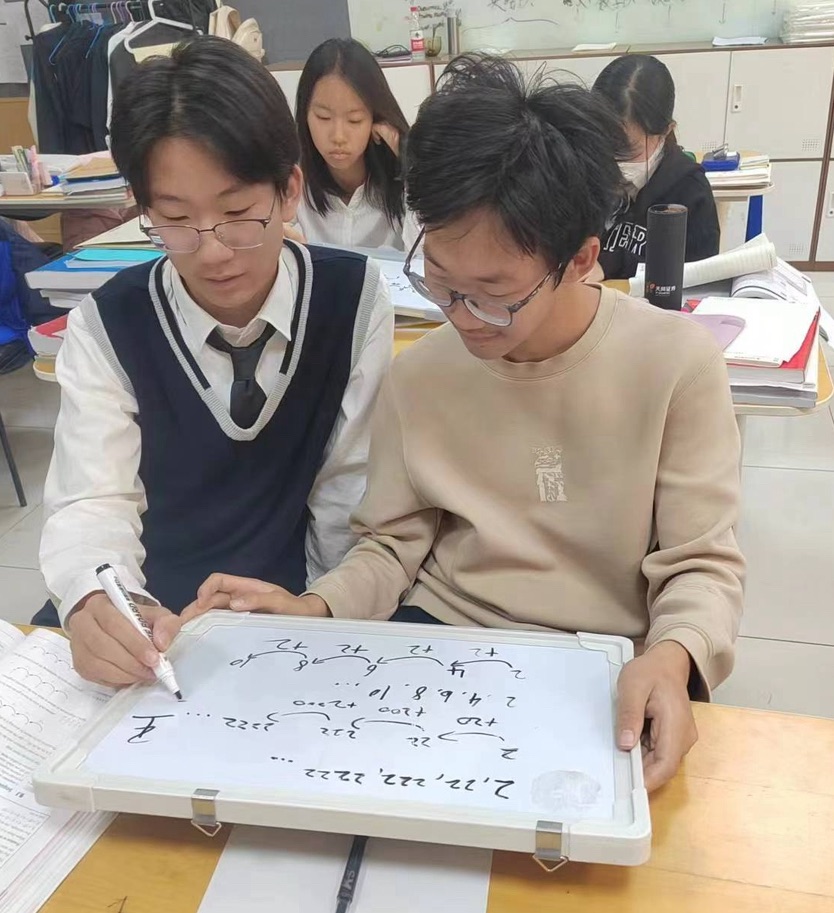

An exchange with China would allow new cultural approaches to be learned. On prime-time Chinese television there are game show competitions for young people built around mathematics. When my IGCSE maths teacher gives out homework he links it into shared culture, ranging from the architectural achievements of the past to the engineering accomplishments of modern China. Students are very ready to co-operate and share their thinking and solve Maths problems together. The result of this cultural capital is that Maths classes in my school often achieve the quality of what I call ‘flow’, where the students are utterly absorbed in problem solving.

On the other hand part of my work for the last ten years has involved training Chinese teachers in international teaching methodologies. I have seen first hand how learning from each other has made such teachers into outstanding practitioners now confidently able to blend the best of the west with the best of the east.

Chinese teaching methodologies are excellent at memorisation techniques, but we have taken this one step further by adding the international strategy of ‘retrieval practice’, requiring students to keep in mind learning from previous topics. Chinese teaching methodologies do develop debate and discussion, but we have extended the skills of our students in this area by placing more emphasis on collaborative learning where students discuss and problem solve in independent teams. Chinese teaching methodologies do support cognitive development, but we have enhanced critical and creative thinking by adding to the teacher toolkit in these areas. There is a very simple but powerful strategy developed in western pedagogy called ‘wait time’, which guides teachers to put in a pause between asking a question and taking answers. This little technique has significantly enhanced the educational benefits of questioning in our classrooms. And it all follows from a simple philosophy. Neither culture has the monopoly on good teaching strategies, so it’s better when we learn together.

Finally let’s come back to cultural capital and an amazing flowing together of Chinese and Western thinking. From my experience the problem of how to motivate young people to become effective learners is just as important in China and in Britain. When I first came to work in Chinese classrooms I was staggered by the phenonomen of students putting their heads down and going to sleep, during a lesson! In the West I was sadly used to many different forms of lesson disruption, but never this kind of quietly checking out of learning. Investigation led me to find out it is a culturally condoned, rather than culturally approved kind of behaviour. It was accepted that if a student believed she or he couldn’t learn it was better to quietly slip into sleep rather than interrupt the learning of the class.

The underlying problem behind the poor motivation of both Chinese and English learners is the question of what happens when students believe they can’t learn. In the West students act up to stop the lesson and / or get the teacher’s attention. In China students fall asleep so that the lesson can continue. Therefore in order to address the cause and not the symptoms, I introduced a set of ideas to change the culture around ‘giving up’.

Answers to this problem can be found in the research of the American professor, Carol Dweck. Carol Dweck developed an educational strategy called ‘Growth Mind-set’. The argument is that students who fail have a ‘fixed mind set’ and believe they cannot learn. Some interpret this as a psychological strategy but I think it’s better applied to improve a school culture.Teachers must assiduously avoid any signals to students that their ability to learn is limited. On the other hand, teachers do everything they can to develop a love of taking on challenges and an attitude of persistence that helps students to never stop believing they can learn and be resilient in looking for a variety of ways to learn and understand.

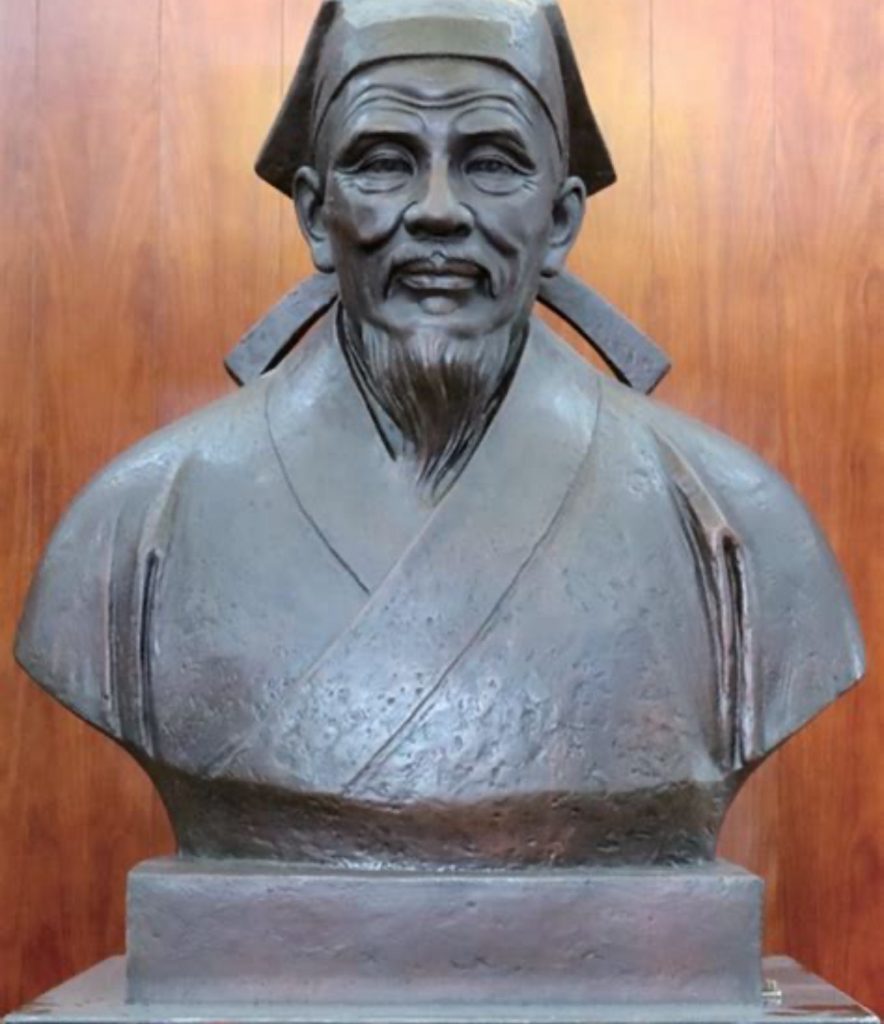

I set about introducing this strategy to my school. I was in the midst of training my Chinese teachers when one of them asked, ‘Are you sure these are modern western ideas, because they are very similar to ancient Chinese thinking’. When I had finished my introduction she came to the front and talked us through a set of ideas in Chinese called ‘daxue’ or ‘Great Study’. The origin of these ideas may lie with Confucius but they were put together in a systematic way by a thinker called Zhu Xi. In essence the principles are:

诚心 – Cheng Xin or Sincerity

勤奋 – Qin Fen or Diligence

刻苦 – Ke ku or Hard work

恒心 – Heng Xin or Perseverance

专心 – Zhuan Xin or Concentration

尊师 – Zun shi or Respect for teachers

谦虚 – Qian Xu or Humility.

As we discussed and reflected on these ideas we agreed that yes, these were all important ingredients of developing ‘Growth Mindset’. The advantage of this is that when we began to talk to our students about developing a better motivational and learning culture in our school we could combine both philosophies. Indeed we find that approaching Growth Mindset through Chinese thinking means that we can benefit from the echoes of these concepts within the cultural capital that our students bring to their learning.

The evidence of my experience of ten years of school leadership in both cultures, is that there is everything to gain from understanding and exchange of educational thinking, and so much to lose from ignorance and suspicion. This gives me the conviction that education isn’t the only area of society where this simple idea holds true.