‘Going along the river during Qing Ming’.

Currently there is a cultural event in China, which the people themselves call 清明, which is put into the westernised pinyin as ‘Qing Ming’. The English translation for this is ‘Pure Brightness’. In this article I will start by introducing some common features of the festival, discuss some similarities with western traditions and then go on to discuss a very famous Chinese painting based around the festival called, 清明上河圖, pinyin: Qīngmíng Shànghé Tú, ‘Going along the river during Qing Ming’.

Like many festivals in China, the origins seem to lie in a mix of history and the environment. One explanation for ‘Qing Ming’ is that it is a memory of China’s agricultural past, because in ancient times this time of year saw a ‘clear and bright’ breeze -a ‘Qing Ming’ that blew over China from the south-west, driving away the cold air, allowing temperatures to rise and rainfall to increase, starting the growing season for new crops. In other Blogs I’ve explained that the solar or agricultural year still plays a prominent role in Chinese culture.

For the historical account we have to go back to the Zhou Dynasty in the 6th century BCE. The story concerns a noble man called Jiè Zhītuī who saved the life of his leader, Prince Wen, seemingly by cutting a piece of flesh from his thigh and serving it in a soup for the starving Prince. Things took a tragic turn when the Prince ordered Jiè Zhītuī to come to court and serve him there. Refusing the royal command Jiè Zhītuī, returned to his home in the Mianshan mountains.

Desperate for Jiè Zhītuī’s help the Prince set fire to the mountain vegetation to drive Jiè Zhītuī out, but instead he burned his follower to death. Full of remorse, the Prince built a temple in the mountains and gave an order that in future no fires should be lit at this time.

From this developed the custom of setting aside this time of year as Hánshí Jié, or the Cold Food Day. Later in the T’ang period ( 628-907 CE) the Emperor Xuanzong (712–756 AD) decided to declare that the Qing Ming day was the only one in the year when people should respect and remember the ancestors.

Another name for Qing Ming is the ‘Tomb Sweeping’ day. To this day it is the custom for Chinese families to use this day to return to their hometowns and carry out ceremonies of remembrance at the graves of the ancestors. This might sound like a gloomy affair, but in China it is warm, sincere and heartfelt event in which every member of the family has a part to play. When the family go together to visit the graves, there is a tradition that everyone must have something in their hand, a contribution to make to the deceased.

At the heart of the activities are two ideas, first that the living have a duty to provide for the spirits of those who have passed and secondly, that by offering gifts, the living will enjoy the protection and guidance of the ancestors. Surely there are echoes of these core concepts in Christianity, with the Easter rituals to remember ‘the one who died that we might have life’.

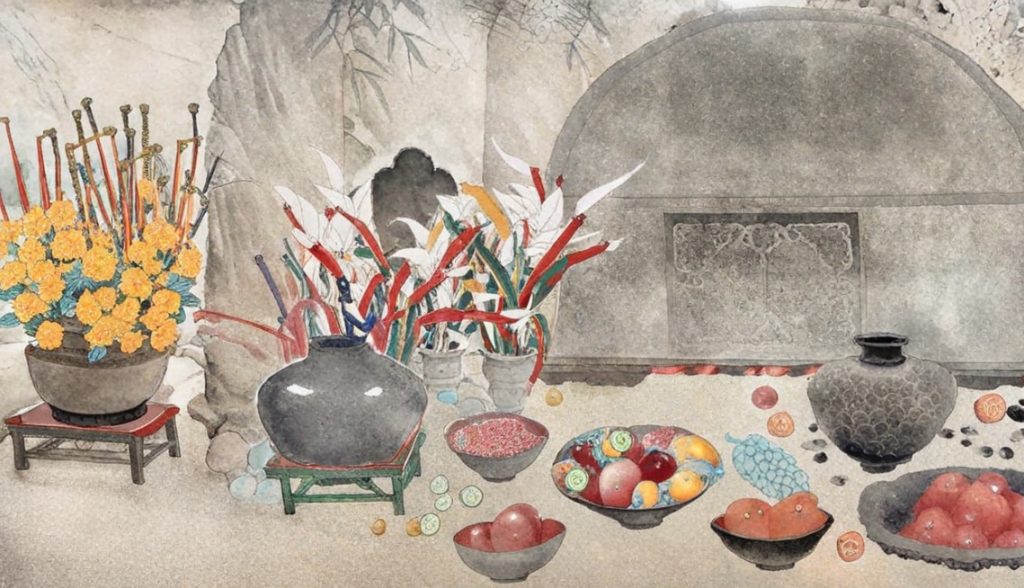

Here are the more common tomb sweeping activities. “放炮” ‘fàng pào’, means setting off fireworks or firecrackers, typically done during important festivals or celebrations. “摆菜”, or ‘bǎi cài’ means arranging some food offerings. “摆花馍馍”, ‘bǎi huā mómo’ are flower-shaped steamed buns are a traditional Chinese pastry often used as offerings. “烧元宝和鬼票子” – both “yuanbao” (paper money) and “guipiaozi” (spirit money) are paper items burned during rituals to symbolize wealth being sent to the spirits or ancestors. Finally “坟头和坟四角填土”, ‘féntóu hé fén sìjiǎo tián tǔ’ is the tradition of adding soil to the top and corners of a grave mound which signifies respect and remembrance of ancestors, and is also a way to seek their blessings for future generations.

Guipiaozi ~ spirit money

Another set of beliefs are around kite flying during the Qing Ming period. There is an idea that at this time the gates between the world of the dead and the world of the living are open. Therefore by flying a kite people can carry their good wishes up to the deceased. Alternatively others believe that kites help to carry away bad luck. People who follow this idea sometimes cut the string of the kite so that any ill fortune is carried away altogether.

Every Chinese festival has strong food associations and Qing Ming is no different. In the south of China the most famous delicacy to eat at this time is called 青团 or qīngtuán. These are green ‘dumplings’ made from sticky rice and barley grass. They will be filled with red bean paste of other sweet fillings. The green colour reminds people of the rejuvenation of life at spring time. In Beijing the favoured Qing Ming foodstuff is called 馓子 or sǎnzi, which are deep fried twists of dough, often arranged in pyramid shapes.

Qing Ming qīngtuán dumplings

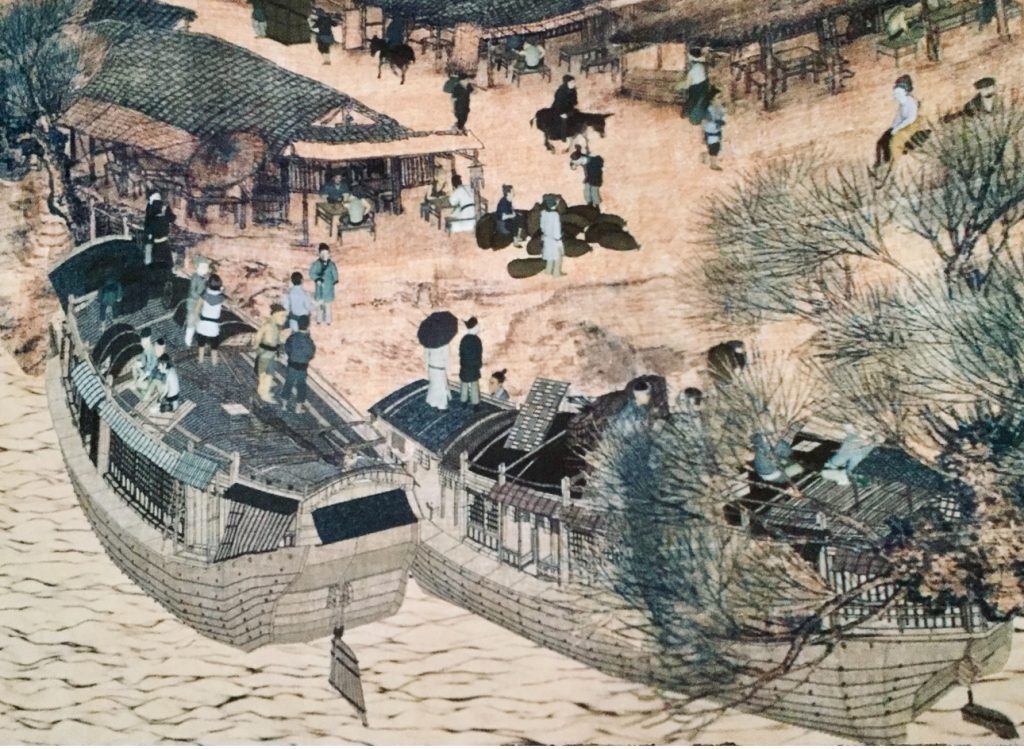

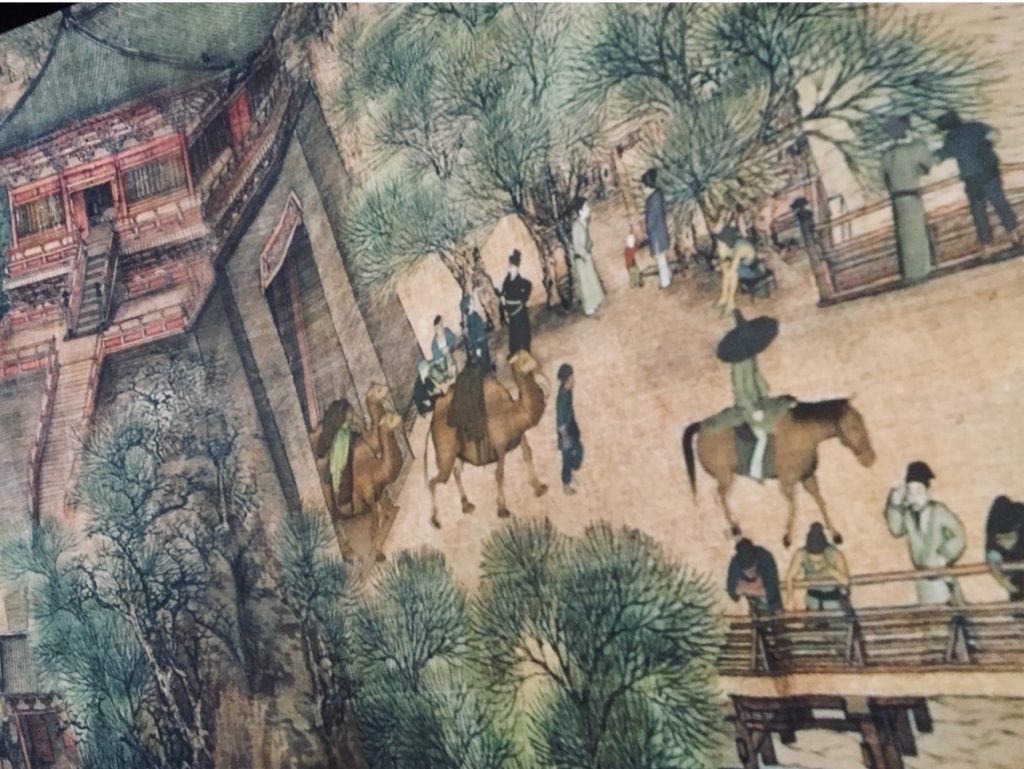

Now let’s turn to the famous painting ‘Along the River at Qing Ming’. I think it tells us a lot about the China of the Song dynasty and the China of today. The painting is a remarkable piece of art. The original is believed to be the work of an artist called Zhang Zeduan, 张择端 . It shows a panoramic view of the then capital of the Song culture, which they called Bianjing, which is now Kaifeng in Henan province. It’s the form of this art work that makes it exceptional. It was created as a hand scroll which unrolls to a length of 528 cm. The idea was that the viewer would unravel it an arm length at a time , thereby recreating the experience of strolling through the city.

The artist chose not to portray the ceremonies of Qing Ming but the way that the ordinary people of the time used the day for meeting, eating, buying and selling. And this will be another important part of the festivities today for billions of Chinese. Whether it’s in small town markets or big city shopping , the Qing Ming scenes all over China will look remarkably similar to the hustle and bustle we see in this painting. To the right hand side of the scroll we stroll through the countryside around the city, meeting farmers and domesticated animals, just as you would today. In the central sections we pass through busy, crowded streets where all the goods and services we might find in a modern city are on offer. At the centre is a great bridge, sometimes called the 虹橋, Hong Qiao or Rainbow Bridge which is the epicentre of the thriving commercial activity. Finally to the far left we see the economic activity which is feeding the city, heavily laden boats loading and unloading cargo and even a merchant caravan of camels possibly arriving from the Silk Road.

In 2010, an electronic version of this painting was created for exhibit in the China Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo. The digitised version now goes on exhibition around the world and everywhere it goes it projects an image of the benefits that peace and stability bring to the lives of ordinary people and their culture. ‘Qing Ming’ has another possible meaning in Chinese which is ‘calm and orderly’, and that is a meaning which I think we can see reflecting in front of this masterpiece of world art. As ‘moderns’ perhaps we get so entranced by the fast moving magical illusions of the present and the future, that we need moments of ‘bright calm’ to reflect deeper into the past and how those now gone have shaped who we are today.

(Images courtesy of the author or CGTN)