First published in China Eye (77) Spring 2023 pages 20-23

3 OCTOBER 2023 | Walter Fung

In 2001, UNESCO made a comprehensive survey to agree on a definition for intangible cultural heritage (ICH). By 2003, a draft stated that intangible cultural heritage is a practice, representation, expression, knowelge or skill. These include nonphysical intellectual wealth such as folklore, customs, beliefs, traditions, knowledge and language. Officials and scholars were concerned that ICH practices and knowledge could be lost to future generations if efforts were not made for their preservation. Historic buildings, monuments and artifacts are considered tangible cultural property. China itself in 2006 and again in 2017, identified 42 items of intangible culture which included aspects of cooking, storytelling, silk tapestry, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the Spring Festival, etc.

The extent to which migrants practise and preserve their homeland ICH in the land in which they settle is a subject for study and research; referred to as ‘travelling ICH’. This short article deals with Chinese ICH in the UK. In a multicultural society such as the UK, knowledge and appreciation of each ethnic groups’ culture and traditions should lead to more tolerance and understanding of each other’s differences.

The Chinese community in the UK is over 400,000 strong, but compared to other ethnic groups, relatively little is known about it. Chinese generally prefer to keep their heads down and tend not integrate with the host community as much as some other ethnic groups. Analysts have referred to the Chinese community as the ‘invisible minority’ or ‘silent minority’. In addition to the resident Chinese there are about 120,000 Chinese undergraduate students and many more post-graduate students and university staff. However, Chinese have a ‘Chineseness’ which is retained not only by new arrivals, but also to varying extents by their children and even grandchildren.

In the UK, Chinese cooking is perhaps the most visible Chinese ICH, but there is also activity in Chinese art, brush painting, calligraphy, lantern making, paper cutting, paper folding, Chinese opera and dance, literature and poetry, tai qi, martial arts, Chinese music and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which includes acupuncture, cupping, moxibustion, herb remedies, massage etc.

Some of the customs and beliefs are carried out only by the Chinese communities themselves and are probably not well known to the host community such as honouring the ancestors at Qing Ming, and respect for authority and for older people. Chinese literature written only in Chinese would not be well-known by those who do not read Chinese.

The Chinese community in the UK is not homogeneous. Individuals may have come from mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao, Malaysia, Singapore and many other places such as Mauritius and the West Indies, but they all share Chinese Culture. They may be British born or born abroad, but when they came here, they may have been children, young adults, middle aged or elderly. All of these factors will affect their knowledge, adherence and attitude to Chinese ICH although, interactions with the host community will tend to dilute some of this.

China has 55 recognised ethnic groups as well the mainstream Han, e.g., Tibetans, Mongolian, etc. In addition, there are Hakka Chinese, who are mainstream Han but have their own traditions. These ethnic groups have their own distinct beliefs, customs, language or dialect and style of cooking. The UK is home to a large number of Hakka Chinese, but people of the ethnic groups are not here in any number. In addition to the Cantonese and Hakka dialects there are significant Hokkien and Teochew (Chaozhou) dialect speakers in the UK. A sub-dialect of Cantonese is Toisanese which is spoken by Chinese from the See Yep area in southern Guangdong province.

The first Chinese settlers in the UK were mainly Cantonese from Guangdong province. They began to arrive in the late 19th and early 20th century. Chinese from other parts of mainland China began to arrive shortly after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms of the late 1970s. However, the Cantonese, which includes those from Hong Kong, still probably make up the largest group of Chinese in the UK. Mainland Chinese generally speak Mandarin, which is the national language of China. The Cantonese and Hong Kong Chinese of course speak the Cantonese dialect

Chinese people are self-reliant and the community tends keeps to itself. In the mid-1980s, the British government was concerned that, many Chinese were not claiming benefits to which they were entitled such as unemployment or sick pay. This is beginning to change somewhat as people of Chinese descent are integrating more and standing as councillors and even as members of parliament

Some traditional Chinese customs are likely to be followed more closely by Chinese from Hong Kong, and places other than the mainland itself, where the Cultural Revolution had a negative effect on traditional culture. Old ideas, culture, customs and habits were prohibited. Reverence for ancestors was curbed but has been revived and Qing Ming is now a National Holiday in China.

In my opinion, one of the most apparent ICH is the Chinese character itself. Chinese are renown for being law abiding, hardworking, respectful of older people and parents, their strong commitment to family, following Chinese traditions and value for education. Chinese children have the highest success rates in UK schools. These attributes have their basis in Daoism, Buddhism, traditional beliefs and especially Confucianism which stresses education, good behaviour, harmony and moderation in all things. The Chinese religions seem to merge, there is no conflict between them. Early Christian missionaries to China were surprised to see people of all religions living happily together.

Fig 1. Chinese brush painting; Summer landscape (Brian Morgan)

Especially amongst the older members of the community there is a strong identity of being Chinese. Chinese will feel more comfortable using a Chinese accountant or lawyer rather than a British one, although communication will play a part. However, these factors are likely to be diluted with second and succeeding generations – or if a British marriage partner is taken. Many Chinese, especially the older generations have a strong attachment to their home village. They never forget their roots. They want to retain their Chinese identity and some succeeding generation regard themselves, as Chinese even though they may be unable to speak Chinese, some may not even look Chinese!

Evidence of ICH in the UK is Chinese schools, and community centres teaching the Chinese language, both Cantonese and Mandarin, Chinese brush painting, music, calligraphy, tai chi, qi gong, kung fu, Chinese dances -including those dances of ethnic minorities – and traditional Chinese handicrafts such as lantern making, paper cutting and paper folding. Community centres include the Wah Sing, Pagoda and Wirral Community centres on Merseyside. There are similar establishments in many of the larger centres of Chinese population such as the Birmingham Chinese Community Centre, the Manchester Chinese Centre and Wai Yin Women’s Association in Manchester. London, in which about a third of ethnic Chinese live, has a fair number of Chinese community centres in Camden, Islington, Barnet, and Lewisham to name just a few.

Chinese cooking is now well-established in the UK and many non-Chinese know how to prepare different schools of Chinese food such as Cantonese, Beijing, Sichuan, Hunan, Hakka etc, each having its own flavours, ingredients and other characteristics.

The most important festival for Chinese people all over the world is Chinese New Year, In China, it is known as the Spring Festival. Chinese New Year is now a major event in many of the cities of the UK, especially, London, Liverpool and Manchester where the local authorities close off streets for the celebrations. (Fig 2)

Fig 2. Chinese New Year in Liverpool with Chinese lanterns and a Dragon parade.

The Dragon Boat racing festival held on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Lunar Year is becoming increasingly popular in the UK and amongst the host poulation The Mid-autumn Festival involving Moon Cakes is also becoming increasing well-known. It is celebrated on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. Other Chinese festivals such as Qing Ming and, Chong Yang are not as well-known amongst non-Chinese. (Fig 3)

Fig 3. Dragon Boat Racing at Salford Quays

For centuries, generations of Chinese families lived, as one historian put it, ‘on the brink of disaster’. The vast majority of people were farmers and fishermen. Factors such as the weather, floods, drought and famine were beyond their control. For a large population, food shortage was a constant problem and indeed a sacred duty of the Emperor of China was to pray annually for a good harvest.

Many lived in poverty throughout their lives and so luck and wealth symbols were constantly displayed in the hope that their circumstances would change. Within the last 180 years, major civil disorders and foreign invaders made matters worse. Consequently, celebrating certain festivals and the belief in luck played an important part in peoples’ lives.

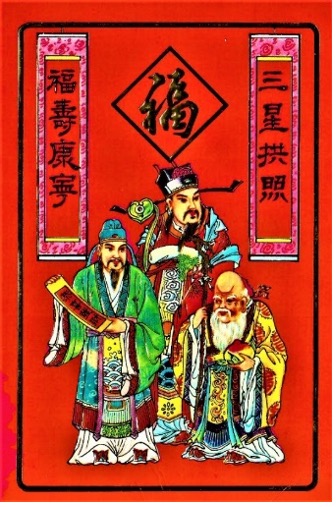

Expectation of life was very low, less than 40 years even as late as 1949 and hence the worship of a god of longevity and for the character for longevity to be displayed in prominent places, such as on, or over doorways and on greeting cards.

Fig 4. Greeting cards; on left the character for long life (寿), written in many different styles. On right, the Three Gods, Luck, Wealth and Long Life. (福, 禄, 寿) (fu, lu, shou)

Superstition was rife in old China giving rise to rituals and elaborate practises. Although today, superstition is considerably reduced and discouraged or even prohibited in mainland China, some rituals continue and are can be regarded as intangible culture. The three gods of luck, wealth and long life are conspicuous everywhere; look out for them in Chinese restaurants, on greetings card, calendars, posters and on doorways.

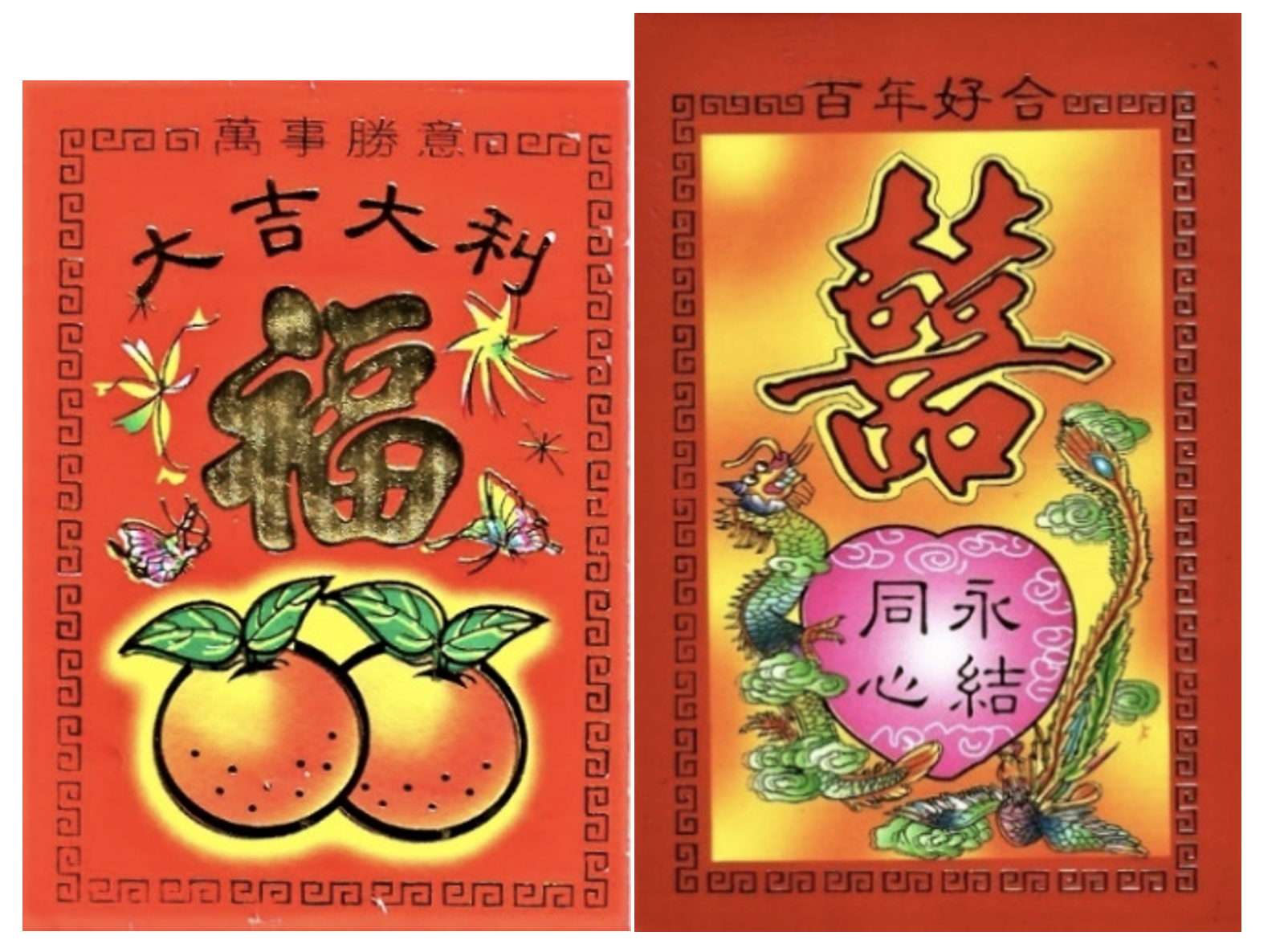

The character for luck is on red packets, which are used to present gifts of money at New Year, birthdays or other celebrations.

Fig 5. Red packets showing the character for luck (left) and with the wedding ‘double happiness symbol (right).

Although the lives of people in mainland China have been significantly improved. extreme poverty has been eliminated and there is no food shortage, some traditions and customs are still adhered to. They are probably carried out more in the UK and overseas Chinese communities than in the Chinese mainland itself and can be regarded as ‘traveling Chinese intangible culture’.

The Chinese equivalent for ‘Happy New Year’ is ‘Gung He Fat Choy’ in Cantonese or ‘Gong Xi Fa Cai’ in Mandarin. This can be translated as ‘Congratulations, may you make money’.

Fig 6. An auspicious shop name

Much can be learnt from the names of Chinese businesses such as restaurants and take-away food shops. This shop sign, ‘Wing Lee’, in Cantonese, means ‘forever profitable’. It probably is not the name of the shop owner. Many laundry businesses in Liverpool and elsewhere had the name Lee incorporated. Some authors believe the Lee clansmen dominated the laundry business, but I suspect that the word Lee was put in because it is a homonym for profit. A Chinese supermarket in Manchester is named.’ Woo Sang’ in Cantonese (和 生), which can be translated as ‘the birth of harmony’ In China, the character for harmony (和), is on every high-speed train. Another Manchester supermarket is called ‘永 發’ (Wing Fat in Cantonese), meaning ‘forever producing (wealth).

Fig 7. A Chinese ‘harmony’ high-speed train in Nanjing

Numbers also have a significance; eight, ba in Chinese, sounds like fa, meaning generate (wealth) and is highly valued by Chinese as part of a phone number, car number plate, house number etc. On the other hand, the number four is to be avoided; it is a homonym for ‘death’. Some symbols or figures of fish, clouds, tortoises or bats for example have a special meaning to Chinese people, but probably not to Westerners. The dragon is probably the best-known Chinese figure followed by the phoenix.

Traditional Chinese will follow certain procedures at the major events in a person’s life: birth, marriage and death. These were extremely elaborate in old China but some are still observed as much as possible and as much as modern living in the UK allows. To celebrate a birth, red eggs may will be offered to family and friends. Certain rituals may be followed and there may be a ceremony at 100 days after the birth. Traditional Chinese weddings may be conducted with the bride wearing traditional red Chinese costumes and there may be a ‘tea ceremony’ where the newlyweds pay respect to their parents and other senior family members. The newlyweds serve tea and the recipients give a red packet in return to the couple.

Some families will want a traditional Chinese funeral which involves certain rituals many based on Buddhist beliefs. Location of the grave was extremely important in old China but in the UK, there are limited options. By tradition, the human body must be kept intact, even in death, and so cremation is not popular amongst Chinese.

Amongst other traditional practices at the Spring Festival, families will clean the house, but definitely not on New Year’s Day itself – good luck may be swept away! Reunion family dinners will be held and children will be given red packets of money. Couplets written on red paper or fabric, wishing good fortune, good health or prosperity will be hung on walls and around doors.

In the larger centres of Chinese people such as Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and London, there are Chinese organisations which provide community services but also foster and encourage Chinese customs and heritage. In Liverpool there are neighbourhood associations; See Yep (Four Counties), Hoi Yin, Tap Mun and there is the Chinese Freemasons. At the Chinese New Year, they generally organise a dragon parade, lion dances and other celebrations. Chinese New Year is a good time to demonstrate Chinese culture such as tai qi, calligraphy etc to the local host communities.

In Liverpool the See Yep and the Freemasons organise visits to the Liverpool Chinese cemeteries at Qing Ming and Chong Yang, to pay respects to dead relations and ancestors. Chinese groups in other centres with significant Chinese populations also organise similar cemetery visits. In addition, there are a number of clan associations in the UK who maintain the tombs of family members. As well as placing flowers on the graves, some families will also ‘offer’ fruit and food, usually roast pork, to the ancestors. Paper money may be burnt as tribute and joss sticks lit.

Fig 8.Liverpool See Yep Association about to visit the Chinese cemeteries.

Certain concepts underpin Chinese thought. Prominent are the duality of yin and yang, chi (qi) and feng shui. These concepts have no equivalents in Western science or culture. Yin and yang are equal and opposite forces, which are present everywhere and in every situation. In living beings Yin is female and yang is male. Hot is yang and cold is yin. Yin is passive, yang is active. One cannot exist without the other; without cold, hot has not meaning. They are not static, but constantly changing. They are direct opposites but they must always be in balance for harmony.

The concept even applies to food; bananas, beans and oranges are yin (cold), beef, chicken and walnuts are yang (hot). My father used to refer to foods as ‘hot’ or ‘cold’ (‘lieng’ in his dialect of Cantonese), and in preparation of meals, kept them in balance, and consequently our family had a good diet. An excess of one type of food can upset the balance in the body resulting in illness or discomfort. Well-being can be restored by eating the appropriate food or taking appropriate herbs to restore the balance.

Fig 9. A ‘bagua’ octagon with the yin yang symbol of balance in the centre. Each contains a seed of the other. The trigrams are used in divination. An unbroken line represents heaven, a broken line, the earth. (Reference; The Yi Jing)

Chi can be described as the flow of life’s energy or cosmic energy. It must flow unimpeded and in the appropriate quantity for a given situation. It is everywhere, on the land and sea, within plants, the human body and indeed in that of all living beings.

In Chinese medicine, chi is believed to flow via meridians in the human body. If the flow is impeded or is not appropriate to the prevailing environment, the person feels ill. The task of the medical practitioner is to relieve any blockage and restore the flow of chi. This can be done by a variety of techniques in Chinese traditional medicine such as aquapuncture, massage, ‘cupping’, administering herbal preparations etc.

Early Chinese philosophers believed in the universal connection between man and nature resulting in the concept of yin and yang. In addition to this, was the concept of the five elements, sometimes referred to as phases: earth, wood, metal, fire and water. These are ‘headings’ and do not necessarily refer to the material itself. Wood for example is associated with trees and plant, paper and the colour green. Fire represents, candles, lamps and lights, man-made materials and the colour red. All the various body parts are associated with one of these elements, e.g., the eyes with wood, the tongue with fire, the mouth with the earth etc.

All living beings and materials contain these elements which must be present in the correct quantity and must be in balance with each other. It is notable that other human cultures have a similar concept, e.g., Hindu.

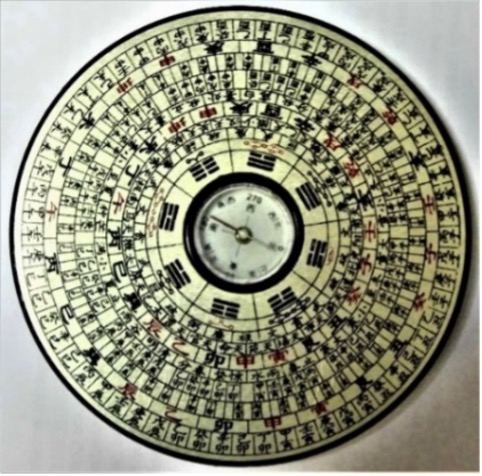

Feng shui, which translates as ‘wind and water’. has been called Chinese geomancy and is a concept in the search for harmony. Yin and yang, chi and the five elements are amongst the factors determining feng shui. There are a number of schools of the practise of feng shui. Most use a feng shui compass, other schools use more advanced and specialised considerations such as the position of the stars and constellations.

Fig 10. A feng shui compass

Feng shui influences the environment and surroundings, a persons’ health, temperament, outlook on life, success in life, happiness and in fact everything associated with his or her existence. Believers in feng shui will consult a feng shui practitioner when deciding on a location for a building. If the feng shui is not right, those persons living or working in the building could feel unhappy, suffer frequent illness and their work will be below par. Needless to say, the company or business is not expected to prosper.

Feng shui has become a popular ‘fad’ in the US, UK and other parts of the Western world, especially since the 1970s. Some attribute this to the interest in Chinese culture following the resumption of US-China relations after President Nixon’s visit to China. Others associate it with the ‘new age’ concepts which arose at about this time. Private companies such as Shell. Esso and eminent individuals such as Donald Trump, Tony Blair and David Beckham have been known to consult feng shui practitioners when deciding on a location, design and other factors for their buildings. Roger Davis, head of Barclays UK banking, in The Sunday Times of 22/5/05, was said to be having his new office feng shui’d as was his office in Hong Kong.

Feng shui is also to be considered when positioning doors, windows and even furniture inside the house, especially the bedroom. Much has been written about feng shui in the garden, selection of plants, position of pathways etc. There are guidelines for feng shui in the office for the business to prosper. Popular feng shui can involve the position of mirrors, water fountains, wind chimes etc, which can enhance good energy or deflect negative energy depending on the positioning of items or circumstances.

A whole industry has grown up around feng shui. Practitioners, consultants and experts make a good living from their knowledge. Commercial enterprises manufacture artifact and objects claimed to influence feng shui, such as indoor fountains, waterfalls and wind chimes. There are even feng shui magazines which provide the latest beliefs and interpretations of feng shui in the modern world.

Intangible Chinese culture in the UK is active and widespread and is kept alive by certain organisations and individuals and especially by courses in Chinese Studies at several UK universities, including Cardiff, Leeds, Oxford, Cambridge, London, Manchester and St Andrews. The Confucius Institutes hold courses and talks on Chinese culture and instruction in activities such as tai qi, calligraphy as well as classes in both Cantonese and Mandarin. Chinese opera societies, including Beijing, Kunju and Cantonese styles, exist in London, Liverpool and other places.

In Liverpool the Chinese Youth Orchestra based at the Pagoda of a Hundred Harmonies has a national and an international following. The orchestra performed at the Shanghai World Exhibition in 2010. The Centre for Contemporary Chinese Art in Manchester provides opportunity for Chinese artists to develop and exhibit their creations.

Fig 11. The Liverpool Pagoda Chinese Youth Orchestra (Courtesy of Zi Lan Liao)

In London, the British Chinese Heritage Centre managed by the Ming-Ai (London) Institute, organise projects and courses that preserve and exhibit Chinese culture. Courses include language classes, painting, calligraphy and cooking. Cultural talks are offered on topics such as Chinese classical literature and philosophy. School visits and teacher training and online workshops are available. Their website includes digital exhibitions, cultural information and recordings of interviews and oral histories of British Chinese people from various age-groups, backgrounds and occupations.

In addition to the ‘official’ organisations, there are informal personal networks of Chinese poets, playwriters, authors, artists, musicians etc. All are contributing to the propagation and preservation of Chinese culture and heritage in the UK.

Chinese people seek harmony and balance in all things. Intangible Chinese Culture is contributing to diversity in the UK and has enriched and benefitted British life. Chinese cooking is now an integral part of the British diet. Chinese New Year celebrations are well attended in the large cities. Many enjoy, Chinese recreational activities including brush painting, mah jong and the game go. People in Britain have experienced health benefits from tai qi and qi gong exercises and TCM, especially acupuncture, which is used as a remedy for certain ailments and as an anaesthetic. Although some people are sceptical of TCM, the comment has been made that many do believe in it, especially those who have been cured by it!’.

Some Further Reading

Ball Pamela The Essence of Tao. Eagle Editions, Royston 2004

Flower Kathy, Culture Smart, China, Kuperard London 2010.

Hoyland Kate, Food Culture, China Now No 149, Summer 1994, p14-15

Gao Dr Duo, Chinese Medicine, Thunder’s Mouth Press, New York, 1997.

Hale Gill, The Complete Guide to Feng Shui, Hermes House, Anness Publishing, London 1999

Lee Siow Mong, Spectrum of Chinese Culture, Pelanduk Publications, Selangor, Malaysia 1987.

Leeming Margaret and Man-hui May Huang, Chinese Regional Cookery, Rider London 1983

Liao Yuqun, Traditional Chinese Medicine, China International Press 2008

Lim SK, Origins of Chinese Opera Asiapac, Singapore 2010

Liu Junru, Chinese Food, China Intercontinental Press, Beijing 2010

Palmer Martin, Yin and Yang, Piatkus, London 1997

Qian Minjie, Intangible Culture-Passing on the Tradition, Foreign Languages Press Beijing 2007

Sterckx Roel, Chinese Thought, Penguin Random House, 2019

Too Lillian, Personalised Feng Shui Tips, Konsep Books, Kuala Lumper 1998

Wei Liming, Chinese Festivals; traditions, customs and rituals, Cambridge University Press 2016.