Before SACU was set up in 1965, there had been a series of organisations concerned to develop closer understanding between the British and Chinese peoples. Jenny Clegg surveys the history of the UK friendship societies with China.

The UK-China friendship organisations established throughout this century have each had their own characteristics, yet a common thread can be discerned. These ‘people’s organisations’ opposed British government interventionism and hostile policies, and at critical moments were capable of rousing broad support. Operating as centres for information about the China issue, they worked closely with other organisations – trade unions, peace groups, women’s groups, co-operative societies, Chinese community groups, science and arts associations – supplying speakers and co-ordinating actions.

The roots of this activism are to be found in Chartist opposition to the first Opium War. Chartist leaders predicted the ultimate success of the Chinese people against imperialism. This hope was, some twenty years later, to inspire a young British naval officer, named Augustus Lindley, who resigned his commission to fight on the side of the Taiping peasant rebels. In 1863, aged only 20 Lindley engaged in the dramatic capture of one of Britain’s best Yangzi gunships, the Firefly, which was handed to the Taiping leaders. Lindley’s two volume ‘History of the Taiping Rebellion’ undoubtedly left a mark of anti-imperialism within the British Labour movement – a legacy ignited by the ‘Hands Off China’ campaign of the 1920s.

The ‘Hands off China’ Campaign, 1925-1927

The ‘Hands off China’ campaign grew from 1925 to 1927 in opposition to Britain’s suppression of China’s rising nationalist movement. Support for a strong Chinese people’s government was recognised by British workers, concerned over cheap Chinese labour, as the only chance for a Chinese trade union movement to improve conditions of labour.

Labour activists joined anti-imperialist campaigners to condemn the killings of unarmed Chinese demonstrators by British forces. The British Labour Council for Chinese Freedom, sponsored by the London Trades Council and chaired by George Hicks, also chair of the TUC General Council, was the first organisation in Britain formed exclusively to raise the China issue. It had great effect, uniting Labour and Trade Union leaders in the call of ‘Peace with China’, mobilising hundreds of local trade union and political groups.

Labour leadership demands, however, fell short of troop withdrawals. But anti-imperialist commitment was clear at the grass roots: over 80 ‘Hands off China’ committees around Britain supported demands for recognition of China’s national independence; the end of unequal treaties and extra-territorial privileges; withdrawal of armed forces; and closer co-operation between the British and Chinese trade union and labour movements.

League Against Imperialism, the Friends of the Chinese People, 1927-1937

After 1927 these demands were upheld by the British section of League Against Imperialism (LAI), chaired by Fenner Brockway MP. The LAI British section continued to criticise the reinforcement of Britain’s military presence in China. They opposed the supply of arms to Chiang Kai-shek and the policy of Anglo-Japanese co-operation. And they organised demonstrations to try to stop the ships loaded with munitions for Japan which regularly left British docks.

Later, the LAI British section set up the ‘Friends of the Chinese People’ and tried to involve a number of prominent figures. Throughout 1934 and 1935, it produced China News to provide information in Britain about China’s Red bases, the 8th Route Army and the Long March.

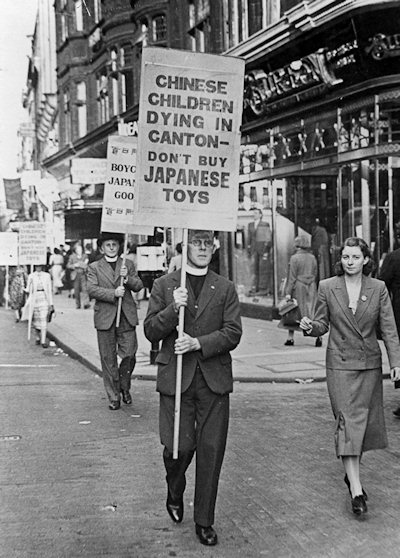

Early China Campaign Committee (CCC) poster rally in London against Japan.

China Campaign Committee, 1937-1949

The CCC was a broad committee mobilising support among British people in aid of China following Japan’s invasion in 1937. It drew together politicians, local councillors, Church leaders and ministers, trade councils and trade unions, co-operative societies and peace organisations in calling for relief to China and a boycott of Japanese groups.

An immensely active campaign, by1940 the CCC had organised nearly 3,000 events throughout the country, including rallies, meetings, cultural evenings, and poster parades and had distributed one million leaflets. The strength of the campaign was really demonstrated by its success in preventing the loading of ships with materials for munitions to Japan.

Funds raised by the CCC went to Mme Sun Yatsen’s China Defence League in Hong Kong for the International Peace Hospitals in the Liberated areas. In 1942, the Committee sponsored the Anglo-Chinese Development Society to channel support from the British Co-operative movement for the Gung Ho industrial co-ops which operated. in both KMT and CCP-controlled areas.

In 1942, when the British United Aid to China was set up with official British government support, local CCC groups joined in with their fund-raising energies. However, the BUAC council abandoning neutrality, preferred to supply the KMT whilst avoiding sending relief to the Liberated areas.

Britain-China Friendship Association, 1949-1960s

The Britain-China Friendship Association was the main source of public information about all aspects of China’s internal developments and her stand on external issues throughout the 1950s. The organisation was formed drawing together three key constituencies who saw the PRC’s establishment as a new opportunity for developing links: the co-op movement; people in scientific and cultural fields; and the trade unions, hoping to establish the close links sought by the British Labour Council of Chinese Freedom in 1927.

The strength of the BCFA came from a core of activists in its individual membership which reached over 2,000 at its peak; an affiliated membership of around 400,000 through some 80 supporting organisations; and such authoritative figures as Joseph Needham and Joan Robinson who placed the Association at the forefront of cultural and academic exchange with China.

The BCFA constantly criticised British complicity in US policy towards China: support for Chiang Kaishek and Taiwan, the exclusion of China from the UN, and the Korean War. Public reaction against British embroilment in war with China in 1951, and again in 1955 and 1958, gave impetus to the British peace movement and the BCFA undoubtedly played an influential role in this. Only the BCFA had the expertise to respond to the tremendous call for information and speakers with first-hand knowledge from peace at local levels.

The China trade embargo was a further issue of public concern. Britain’s commercial interests in China in 1949 were far greater than that of any other Western country and the US-instigated policy was widely seen to be costing British workers jobs. The legendary efforts of the British businessmen in the ‘Icebreakers’ mission and the ’48’ group, whose key figures were active in the BCFA, won support amongst trade unionists who saw trade with China, not arms manufacture, as the way to help Britain’s economic difficulties.

SACU, 1965 to present

Formed at a time of confusion amongst the British Left, after the Sino-Soviet split, SACU adhered to the view that friendship with China could only really be based on genuine understanding. Seeking not to preclude constructive comments and sympathetic criticism, SACU set out to tackle misconceptions by ‘showing China as she really is’.

SACU’s launch had the support of over 200 distinguished names in the arts, sciences, public life and academia. Within months, however, Sino-British relations began to seriously deteriorate. The British Hong Kong authorities’ suppression of the mass protests against the country’s use as a US base in the Vietnam war was followed by the burning of Britain’s Beijing Embassy. Then scuffles in London erupted as police harassed Chinese embassy staff. Many eminent sponsors fell away as SACU firmed up its stance to oppose hostile policies and campaign vigorously against the ‘yellow peril’ scare misrepresenting China as the new world menace.

SACU grew as the Cultural Revolution and China’s stance on the Vietnam War stimulated new interest. Once full Sino-British diplomatic relations were restored in 1972, SACU continued its valued role in providing informed discussion about China’s world view and experiments in social change. This fed into debates in the women’s movement, black and anti-racist groups, the shop stewards’ industrial democracy movement, as well as the arts and medicine.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, SACU helped to initiate links such as the twinning of Birmingham and Changchun in 1981. As contacts between China and Britain expanded, SACU adapted its focus to educational and cultural activities. The success of tours between 1977 and 1987 helped to sustain the growing library and magazine, China Now, which since 1970 had been at the forefront of debate about China. At the time of the traumatic events of 1989, SACU’s membership was at its highest ever. Nevertheless, internal financial problems led to the closure of the London office and a move to Cheltenham.

Looking back on this history we can see the strength of these organisations was in their ability to articulate the common interests of British and Chinese people – in peace, economic relations, cultural exchange and two way learning. As, in the new millennium, we turn to issues of global interdependence and sustainable development, this provides something to consider.