This interview with Professor Michael Wood, SACU President, on Du Fu and China, was published in Chinese Social Sciences Today (a Chinese language newspaper) on 10 December 2020. Felicia Hong JIANG was the interviewer and the article was published in Chinese. We are grateful to Michael for sending us the text of Felicia’s questions with his replies.

1 How is your new book The Story of China related to and different from the documentary series of the same name in 2016?

Films do very different things to books. Obviously in a 600-page book you can do a great deal more than in a film. You can put much more in, expanding the material with richer context, argument and nuance (which TV rarely does well!) and you can take time over the big ideas. It also allowed me to look in detail at some of the great stories we could only touch on in the films; for instance, important cultural figures like Li Qingzhao or Cao Xueqin, or little known but fascinating female writers like Zheng Yunduan, Fang Weiyi, He Zhen and so on. The book also looks at some important discoveries only published in the last few years, such as the new Qin and Han legal documents, the Qin soldiers’ letters from the Conquest period, or the Han letters from waystations and watchtowers on the Silk Road. People’s voices are a very important part of the book.

2 What inspired you to make the China documentaries and publish the new book?

As I’ve said I was interested in Chinese culture from schooldays. At university I shared a house with a Chinese scholar who was always lending me amazing books. After my postgraduate research I went into TV; I first went to China in the early eighties and first filmed in China in the late eighties. My wife Rebecca and I are part of a small independent company Maya Vision, and since then we have made many historical cultural and political documentaries which have gone all over the world, some to 150 countries and territories. Among our history series was The Story of India (2007) and after that everyone said, ‘you have to try to do the same for China!’ So, it was some time in gestation. We have made many history films, but many cultural ones too (among them a 4-part series on the life of Shakespeare (my biography is published in China), a recent film on the great Roman poet Ovid, and other films about early English culture. So, films on poetry and literature are also part of what we do, and when we made The Story of China, we included many sequences on culture with stories of famous Chinese writers and poets. The ethos, the spirit of a civilisation, I always feel, comes out strongly in its poetry and literature.

3 Given the immense period of time of the Chinese civilization, how do you decide what parts to be included in the book and the documentary?

All historical writing is an act of selection; the art is selecting so that the whole feels like an organic whole and tells a narrative that flows and makes sense. With films this is all the more so – films are very compressed narratives. Now, obviously, Chinese history is so big that the selection is everything: my book is 500-600 pages long, but you could write that much on Du Fu alone!! As the book is intended to be an introduction for the general reader, the idea is to present a narrative that gives the general reader in the west a sense of the immense scope and scale and richness of Chinese history; the big themes that run through time; the continuities and the periods of disruption: it’s a tale of incredible drama, creativity and humanity: that’s what I wanted to convey to the reader here who perhaps knows nothing or very little about the story.

That said you then follow your own particular interests. For example, I was concerned that the book included some great women’s stories. Recently we have had interesting books on say Dowager Cixi, a film about Empress Wu, but I went for figures less well known here who have left wonderfully intimate writings – as I mentioned before, Li Qingzhao, Zheng Yunduan, Fang Weiyi, the women in Zhang Xuecheng’s biographies, or the feminists in the late Qing like Qiu Jin, and He Zhen, whose feminists manifesto has caused a lot of interest over here. (*See the preface to my book for more on this).

4 China is the oldest living civilization on earth. What forces have kept China together for so long?

A huge question! A short answer: Confucius in a famous passage in the Analects talks about ‘this culture of ours’ and that idea has been with Chinese people ever since through thick and thin, despite sometimes huge breakdowns – e.g. at the end of the Han, or end of the Tang. The belief that Han culture and civilisation, the script, the core texts containing Chinese values, were the bedrock despite immense cultural and linguistic diversity. Think of Wang Renyu on the chaos of the Five Dynasties (a tale told in the book), or Lu You in the Southern Song lamenting China’s divisions: these core ideas were very ancient. As it says at the beginning of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, ‘The empire that falls apart will come back together again’.

5 Why was China overtaken by the West after the 18th century?

It’s a long story on which many books have been written! In brief, historically speaking it was a ‘perfect storm’: the rise of small aggressive maritime powers on the Atlantic seaboard, mercantile, individualistic. Then the European Conquest of the New World, the dispossession of its indigenous peoples, and the exploitation of its resources; then industrial revolution powered by coal allows them to take the lead which until then China had possessed. To this I would add the arms race inside Europe (where there were constant wars through the 17th and 18th centuries) which meant that the West overtook China in military technology; the Qing rulers had no real incentive to develop military and naval technology until then as they had no competitors in East Asia to push them. Add to that the Western conception of secular science-based modernity which they imposed on the traditional civilisations, whether India, China or the New World. Finally, there was also the imperialist/colonialist mindset: Chinese civilisation did not believe in conquering non-Chinese nations and peoples: as Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) noted in his diary in a fascinating passage: their goal was to maintain civilisation within their own borders.

6 How do you understand the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation? What lies behind China’s rise today?

It depends on which timescale you want to look! (Nothing is new in China!) After all, the Donglin reformers talked about national rejuvenation in the early 17th century and there are continuities between them and the later intellectual and cultural renewal movements in the south, like the Fushe movement, the Changzhou School, and the Guizhou modernisers (brilliantly illuminated in the West recently by Jerry D. Schmidt in his fascinating book on Zheng Zhen and the rise of Chinese modernity.) John Fairbank’s terrific book is called The Great Chinese Revolution 1800-1985. What this means is that historians (whether in China or the West) see a long trajectory of change: so, the 1949 revolution was born in the short term over four decades, but also over four centuries. When you ask about what lies behind it, I would put first the solidarity, patience, creativity, energy and hardworking ethos of the Chinese people themselves, their love of their culture, and their deep-rooted sense of justice, fairness and equality. But I would say the key moment for the China Dream was the liberating of the potential of the Chinese people by Deng Xiaoping. Of course, 1949 is a massive turning point in history; but the key moment of change historians will see as summer 77-spring 79, the subject of my five recent films for China Review Studio. China at that point was impoverished and backward and exhausted by social conflict. So the decisions taken by Deng then – in education, agriculture, economy and industry – would transform China: some scholars in the USA that I talked to for the films, like Ezra Vogel (author of the best biography of Deng in the West, which is available in Chinese) argue that (despite the disaster of 1989) Deng is the greatest world leader of modern history, and the Reform and Opening Up one of the most significant events in world history. Everything that has happened in China since has flowed from that. But the biggest credit goes to the Chinese people themselves.

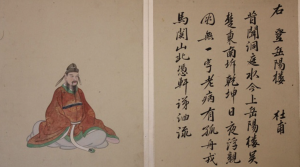

7 You mentioned that Du Fu caught your attention when you were a teenager. Will you please share with us more of that story?

I was interested in him since I was at school when I read a book of translations from Tang poetry – and have been fascinated ever since. We had done a sequence about Du Fu in our BBC series The Story of China in 2016-17. After the warm response to that series, I was intrigued by the idea of trying to bring Du Fu to a British audience for the first time – and also if it could be shown in China too that would be great. Audiences in China had been very generous in their feedback about The Story of China, and I was keen to film back in China with our brilliant Chinese film crew whom we like to work with very much indeed. So, having made the Ovid film we thought it would be very interesting to try to tell his story. One thing led to another, and we made Du Fu as a CCTV/BBC co-production.

Also of course I should say I was curious too, as you must be when you make films, to explore his story further; to see the cottage in Chengdu, visit Baidicheng, and of course to go to Anding near Changsha – a Chinese friend’s mum and dad live nearby in Pingjiang and they told me about the Qingming Festival commemoration at Du Fu’s tomb. I couldn’t wait to go there! This autumn I have prepared a little book full of text and photos called In the Footsteps of Du Fu following his journey round China: we are just about to look for a Chinese publisher – my offering to the spirit of Du Fu!

8 Du Fu is called “The Saint of Poetry” in China. Li Bai, known as the “Immortal Poet”, ranks alongside Du Fu as one of the two leading figures of Chinese poetry. Why do you consider Du Fu as the greatest Chinese poet?

Of course, all Chinese people put them together. Two sides of human nature almost – as we would say the Apollonian and the Dionysian! But what I meant by this is that when we call Du Fu ‘China’s greatest poet’, much as we say Shakespeare is the greatest poet in English, it is the amplitude of his works that is so striking: the amazing range of his poetry from huge vistas of war, his great speculations in the Gorges on human beings’ relation to nature, landscape and the cosmos, to the close-up intimacy of family, friendship, eating together, making a chess board out of old paper. Everything in life is the subject of his poetry. So, it is his wide-ranging imagination which makes us think of Shakespeare. And like Shakespeare in English, as Stephen Owen says in our film, Du Fu not only wrote ‘the greatest words in the Chinese language’ but he also helped create ‘the moral and emotional vocabulary of the culture’. What is important is his lifelong belief in Confucian virtue, benevolence and righteousness – it seems to me these still matter, despite all the disasters of the 1950s and 60s; they are still fundamental to how society works, and how people act towards each other: these are ‘what makes society tick’, as we say. He writes very movingly about friendship and family – he writes lots of poems about eating and drinking (one of the big things the Chinese people love of course is eating and drinking together with family and friends!!) So, though he died in obscurity, in the 9th century his poetry began to be known, in the 10th century his fame grew, and by the 12th century he was viewed as the great poet; from then on, in the Confucian revival of the Song, he crystallised in beautiful language the values of the civilisation, and that passed right down to modern times. Even today. I saw in an interview that President Xi, when describing his time in re-education as a teenager near Yan’an, said his consolation was Tang poetry, and especially Du Fu.

9 Sinologist Nicolas Chapuis said Du Fu is to China what Shakespeare is to England. What do Du Fu and Shakespeare have in common?

Nicolas Chapuis (who is also EU Ambassador to Beijing) is part way through a huge project to publish the whole of Du Fu’s work in French, with a very helpful and detailed commentary. So, after the first complete edition in Chinese in 2014, then Stephen Owen’s complete English version in 2016, we now have a really wonderful French edition distinguished by its rich and helpful commentary which draws not only on nearly a millennium of Chinese commentaries but also on almost 200 years of western scholarship. What we are seeing then is the growth of a global vision of Du Fu as a poet who transcends the boundaries of translation and becomes a universal voice like Shakespeare – as Chapuis says in the preface to his book ‘a voice that lives today with a clarity and power that cannot but astonish’.

A footnote: Chapuis has an interview online which I like very much: he talks about the Chinese writer Qian Zhongshu (whom he knew) and his Guan Zhui Bian (translated into English as Limited Views): this masterpiece exposes the missing links between China and the West. Qian was fluent in English, French, German, Italian. What he showed in Guan Zhui Bian is that there is no separation between East and West. The gaps are totally arbitrary. You can use Chinese texts to understand Western philosophy, and you can use Western philosophy to understand Chinese texts. Because he concentrated on the human condition – what it means to be human. He showed that of course there are differences in approaches and perceptions, but culture is global. Many of the things that China thinks are unique to China are not. It is global; it is human. It is in poetry that you find human nature. And Chinese poetry has always been about the individual, the personal.

10 When creating the Du Fu documentary, you traced the journey on the Chinese ground. Has this journey made you see Du Fu from a new light?

You always learn something new when you travel, and especially in China which is so rich in landscape, people, culture and customs. And of course, focusing on Du Fu alone for a while you couldn’t help but understand more about the culture as a whole, and its enduring values which are still there despite all the huge changes of the last seventy years.

The plan was to follow his path, as it were. We at Maya Vision have made many films on culture and history, and often we have adopted the idea of weaving the story round a journey, which is a more dynamic way of telling the story – and of course of moving the camera. Some of our big TV series have taken the form of what one newspaper called ‘History-Travel-Adventure’. For example, we did a series following the story of Alexander the Great from Greece to India through Iran, Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and later a series on the Spanish Conquest of the New World, in Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, and Amazonia: some with very dramatic journey sequences, even hair-raising at times!! These were each seen in over 140 or 150 countries and territories. Even when we made our Shakespeare series – and unlike Du Fu Shakespeare was not a traveller (he lived most of his life between Stratford and London!) we livened up the narrative with travel sequences, e.g. sailing across to Holland for the wars between the Dutch and the Spanish in the 1590s. Du Fu’s life obviously lent itself to that kind of approach, as in the last dozen years of his life it takes the form of a great journey, from Xi’an to Tianshui, over the mountains to Chengdu, then down to Baidicheng, Jingzhou, Lake Dongting, Changsha, and Pingjiang. And to tell it that way gives the narrative a momentum, pushing it forward, which, in any case, is there clearly in his poetry as he travels (‘I am a seagull blown by the wind’). Making the films I felt I got to know him better – by following his route, reading his poems and thinking about them as we went, inevitably you gain more understanding. Some places like Qufu I know quite well – I first went in the 1980s – we filmed there again recently for The Story of China; Xi’an I have been to many times; Chengdu I had never been to, and I really enjoyed going to the Thatched Cottage and meeting people there: it’s a really lovely place to which I hope to return one day. Also, the Yangtze Gorges I had never been to, so it was a great experience to be in Baidicheng – even though the landscape is much changed. The big surprise was how lovely the countryside was around Pingjiang in Hunan, especially along the Miluo river: gorgeous places – the tomb monument at Anding is really beautiful, definitely worth a visit when your readers are down in Hunan!!

11 You are a great success making history accessible to the general public. Can you share with us the key to your success? What makes the Du Fu documentary and The Story of China so appealing to the Western audience?

Thank you, that’s very kind. The Story of China TV series was the main one, and the audience response was often amazement at the stories we told: (‘I never knew that…!’) Also, the audiences here really liked the way the Chinese people came over as interesting, engaged, and great fun: witnesses to their own history. I hope too that the films were appealing because they were made with the heart. Films are basically simple: a combination of pictures, sounds, words and music. But how those elements are put together is the key: with really good editing and use of music, careful choice of words, you can create mood atmosphere and emotion as well as simply giving facts. Rather than being drily factual we also think that films should make the audience feel: so, films should have empathy – an important word. One of the things Chinese audiences said to us about The Story of China films was that they ‘made us feel’. Even Xinhua reviewing the films commented on this aspect, finding the films ‘transcended the barriers of culture and language and created something inexplicably moving’. Films work best if they affect the heart too.

12 Would you please share with us one of your most memorable moments when creating the documentaries on China and Du Fu?

There are so many that I must be brief! In The Story of China so many great moments – the Qingming Festival with the Qin family in Wuxi; the Farmers’ Festival at Zhoukou with a million locals at the shrine of the goddess Nüwa; the wonderful traditional storytellers in Yangzhou; visiting the old Huizhou merchant families in Shexian and Qimen county; returning after so many years to Xingjiao Si – one of my favourite places. With the Reform and Opening Up films two years ago, talking to the farmers in Xiaogang, Anhui, telling the story of their ‘Life or Death Contract’ in November 1978, a turning point in the history of modern China. On the Du Fu film most moving I think was meeting the ordinary people visiting the Thatched Cottage site at Chengdu, some of whom you see in our film: I loved their enthusiasm for Du Fu, and for Chinese culture in general: the little girl reading Spring Rain, the group of ladies, the sweet old local man who said he came ‘many times: at least once every month’ and told us he loved Du Fu because ‘he spoke for the poor, for the ordinary people’. They all seemed to me to be speaking strongly for the enduring values of Chinese civilisation and standing in the rain with them that day in Chengdu I was very touched by that.

The interview was written by Felicia Hong JIANG and originally published in the Chinese newspaper

Chinese Social Sciences Today (CSST)《中国社会科学报》10 December 2020

Or see the interview in Chinese here:

通过杜甫感受中华文明精神特质

——对话英国历史学家、制片人、作家迈克尔·伍德

2020年12月10日 09:20 来源:《中国社会科学报》本报记者 姜红

Interview Michael Wood ChineseSocialSciencesToday