To mark SACU’s golden anniversary this article by Rob Stallard looks back to the events leading up to its foundation using some previously unpublished documents.

SACU’s formation on 15th May 1965 was a significant national event, receiving attention from the national press and the support of a veritable who’s who of eminent people. Bishops; MPs; professors; artists; writers; trade union leaders all lent their names to support the new society. It may come as a surprise to learn that early SACU meetings took place in a House of Commons committee room.

Previous organisations

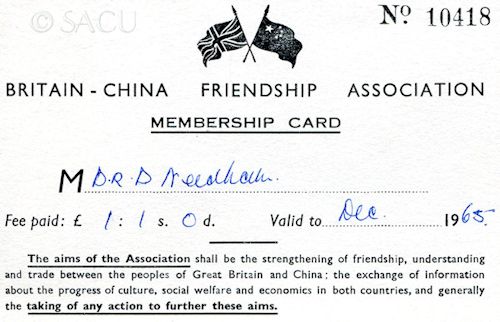

SACU followed in the footsteps of a number of friendship organisations. The British China Friendship Association (BCFA) was founded in December 1949 soon after the People’s Republic had been proclaimed in October. It was the only UK friendly society with good connections with the new government. Agnes Smedley spoke at the inaugural meeting. Joseph Needham took the post of President. Businessmen such as Percy Timberlake; Roland Berger and Jack Perry all joined BCFA and formed the ‘Ice Breakers’ and ‘the ’48 Group’ to open trade with the embargoed P.R.C.

Derek Bryan (1910-2003)

Very often when we think of the foundation of SACU one name springs immediately to mind, Dr. Joseph Needham, however, focusing on the Chairman can mean that the massive amount of work undertaken by the secretary can go unrecognised. So I take this opportunity to introduce Derek Bryan, SACU’s founding secretary, to the story first. Derek went to China in 1932 working at the British Consular Service. It was later in 1944, at the war-torn capital of Chongqing he first met Joseph Needham and it was also at this time that Derek met Liao Hongying, who had studied at Oxford in 1927-36. They soon married and dedicated their lives to promoting friendship with China. His socialist and pro-Chinese sentiments made the foreign office jittery about his allegiances and when they offered him a posting to Peru rather than China in 1951 he decided to resign and return to Britain.

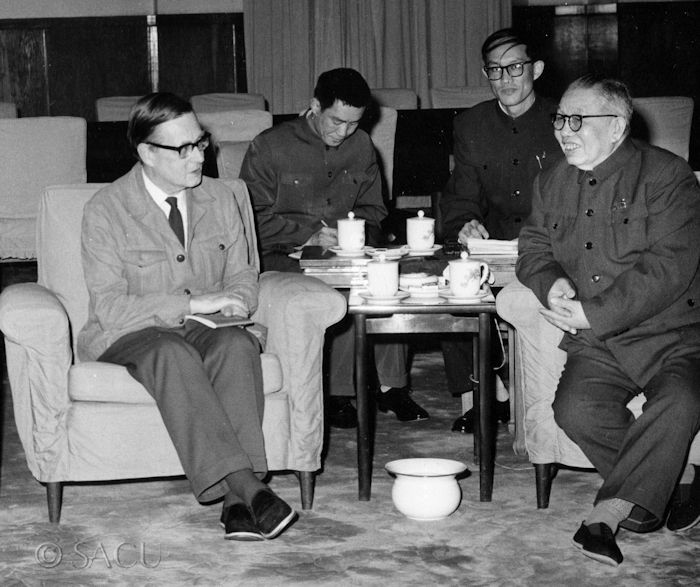

Derek Bryan of the China Policy Group meets Dan Zhenlin V.P. of National People’s Congress 15/04/1977

Derek Bryan became secretary of the British China Friendship Association (BCFA) Cambridge branch 1952-56 where he met up again with Joseph Needham. Hongying and Derek were both Quakers, and a number of Quakers have played an important r?le in SACU to the present day. Derek wrote some recollections of China and SACU for our magazine in 2000 and there is a book by Innes Herdan giving a full and fascinating biography of Liao Hongying ‘Fragments of a Life’.

Joseph Needham (1900-1995)

There has been much written about this most charismatic and quintessential of learned scholars. Here are the bare facts and I encourage you to explore the story elsewhere, most notably Maurice Goldsmith’s UNESCO profile Joseph Needham: 20th-Century Renaissance Man. Joseph Needham first found fame as an eminent biochemist, and in 1941 was appointed as a fellow of the Royal Society for his work. When Lu Gwei-Djen arrived at his laboratory in 1937 he turned his attentions increasingly to Chinese science; language and culture. He made a ground-breaking visit to China in 1943, where he was helped by Zoe Reed’s father K.C. Sun. After returning from China, where he is known as李约瑟 Lǐ Yuēsè, he embarked on what he thought would be a short study of Chinese Science and Civilisation, but it continued to fascinate him for the rest of his long life. Needham was a well known figure on the British Left and supported many progressive causes. In the early 1940s he joined the Cambridge branch of the China Campaign Committee set up to help the Chinese resistance to the Japanese occupation. Needham provided throughout the 1950s one of the only ways to visit China because he retained friendly links with the Chinese government; a young David Attenborough was one who took advantage of this to make his first visit to China. An assertion he made in 1952 that America had used germ weapons in the Korean War caused him many problems. He continued the work to the end of his life at Cambridge where he became Fellow; President and then Master of Gonville and Caius College. The Needham Research Institute has taken up his baton and carries out scholarly research into Chinese culture to this day.

Trouble at the BCFA

The BCFA fell victim to world events, in 1960-62 China broke its ties with the Soviet Union (USSR); Chairman Mao did not want to be under the control of Khrushchev, and suffer the same fate as Hungary in 1956. China had developed its own version of Communism to meet its own needs. This Sino-Soviet split had wide ramifications not just in the USSR and China. Many members of the BCFA were communists and the split forced them to take sides. The BCFA was proscribed by the Labour party and did not have broad left wing support; it decided to follow the Soviet line. It was impossible for Needham to continue close and friendly relations with China and still remain President of the BCFA.

It is important to add some global context to these events. The Cuban missile crisis took place in October 1962; the new U.S. president Lyndon Baines Johnson on 24th November 1963 stated “the battle against communism… must be joined… with strength and determination.” This reversed Kennedy’s more placatory approach during the ongoing Vietnam War. After the Sino-Soviet split, Russia supplied help to China’s enemy India in the Sino-Indian war of 1962. On October 16th 1964 at Lop Nur, China exploded its first atomic bomb; the arrival of a nuclear armed communist state in south-east Asia gained everyone’s attention. America feared China would arm its friends with nuclear weapons and drew up plans to attack China’s nuclear facilities. Johnson sent 3,500 Marines into Vietnam on 8th March 1965 and this increased substantially to 200,000 by December. Most countries, most notably the United States, still acknowledged Chiang Kaishek as the leader of the Chinese government in exile on Taiwan; the PRC did not even have a seat at the United Nations. From 1949 until 1972 Britain did not have full diplomatic relations with the PRC and a trade embargo remained in place. In 1965 with China in a state of total isolation, the stage seemed set for a full scale attack.

Need for a new organisation

The very first documented mention for BCFA’s “metamorphosis into a new organisation” comes in Needham’s letter to the PRC’s Chargé d’Affaires, Dr. Hsiung Hsiang-Hui dated 7th June 1964. Here Needham mentions discussions at a Cambridge BCFA branch meeting and his last, futile attempt to keep BCFA together at the AGM in May.

A number of disaffected BCFA members set up the China Policy Study Group and published a journal called ‘The Broadsheet’. Liao Hongying witnessed how difficult it was to find a united position by reporting “that no-one liked anyone else’s article”.

During the summer and autumn Derek Bryan, Liao Hongying, Joseph Needham and others set up small local groups under the name ‘Friends of China’ at Cambridge; Cheltenham; Manchester and several in London. Meetings were held which invited China experts to come and talk about events in China. The BCFA had concentrated on politics and economics, these new groups wanted to embrace Chinese culture too. There was a passionate debate between those who felt the grass roots movement formed of loosely knit local branches was the way forward and those who thought a high profile national organization was better placed to advance understanding. In the end Liao Hongying was persuaded that the way forward was with a national organization.

The idea of forming an alternative society came into focus when Needham visited Beijing in October 1964 to join celebrations marking the 15th anniversary of the PRC. He was met by no less a figure than Premier Zhou Enlai with whom he continued a friendly correspondence for many years. He also met with the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC). Another crucial encounter was with Joan Robinson, who had worked with the ‘Ice Breakers’ group and was soon to become Professor of Economics at Cambridge; she became an enthusiastic supporter and Deputy Chairman of SACU on its foundation. Needham came back to Britain resolved to make the break.

Resignation from BCFA

We have key documents covering Needham’s resignation as President (he retained his life-membership). His letter dated 26th Jan 1965 sets out his reasoning: “About half the active membership was strongly opposed to the Policy Statement which forbade discussion of the Sino-Soviet dispute, and this part of the Association was then deeply hurt by the refusal of the platform to allow the rebuttal of the accusation of racialism brought against the Chinese” and “…But apart from all this I had long been dissatisfied with the position of the Association in the public life of our country, unable as it always was to exert influence of weight commensurate with the need of the international situation. This, in my view, was caused by its unduly close connection with the British Communist Party, a circumstance which prevented the development of a really broad-based organisation.”

The Secretary of the BCFA, Jack Dribbon, wrote back with words of regret on 3rd Feb 1965. “Your resignation did not come as a surprise to me as I gathered only a month ago this would happen when I had a conversation with some mutual friends. However, I am surprised at your reference to the C.P. [Communist Party]. In our long association, and in our numerous personal conversations, you gave me no indication of your views: Had this been otherwise I am sure many of your doubts would have been easily cleared up. I am sorry you did not mention them.”

However, the personal friendship with Jack Dribbon did not prevent a fairly vicious letter to BCFA members commenting on Needham’s resignation. Dated 15th Feb 1965 it states: “As to his intention to form another organisation we can only say that whereas our intention has always been to preserve the unity of those striving for friendship with China, his proposed move will split the movement and do great harm to the cause of British-Chinese friendship … Dr. Needham says that the Association was always unable to ‘exert influence of weight commensurate with the need of the international situation’ and gives as his reason a supposedly close connection with the Communist Party. This Communist smear tactic is much to be regretted in a man of Dr. Needham’s standing.” The animosity is most evident in the line “We recall a previous effort to disrupt our organisation by founding a new one. This was in the early days of the People’s Republic. It failed. We believe this new similar effort will prove just as abortive.”

The aggressive tone of the letter was counterproductive as it forced BCFA members to take sides. In Needham’s letter to Lord Boyd-Orr (Nobel Peace Prize winner) on 16th April 1965 explains the situation succinctly successfully dissuading him from taking his place as BCFA President. It was the BCFA that soon fell apart and SACU that rose like a phoenix.

Choosing a name

So what to call the new organization? Clearly anything similar to ‘British China Friendship Association’ would cause confusion. There was also the ‘Friends of China’ group; so in actual fact the choice was limited. Luckily we have the memorandum giving Needham’s view and from it we learn something of his mindset and character so I include it in full.

Memo: DB (Derek Bryan); JR (Joan Robinson); JN (Joseph Needham); RB (Roland Berger)

18th March 1965

I have given some more thought to the question of the name of the organisation, and the more I do so the more I prefer SACU as it is.

1) Understanding seems to be agreed on all hands. Gwei-Djen and I have found very interesting and appropriate translations and mottoes for emblem and symbol, and these were sent to RB for the artists a few days ago.

2) The idea that Anglo- excludes Ireland, Wales and Scotland, seems to me far-fetched, and I can’t take it very seriously. Since Anglo-Chinese has never been used for a mixed-blood community that argument seems also weak to me.

3) I greatly dislike double names, and Britain-China is “patented” anyway, in the present situation.

4) I also greatly dislike double adjectives, and British-Chinese or Chinese-British seems to me about as bad as Marxist-Leninist.

5) The only alternative so far mooted with which I could sympathise is Sino-British. My wartime outfit was the Sino-British Science Cooperation Office. I don’t think this is too “academic”; nobody thought so during the war. But I still prefer Anglo-Chinese. And it has the strong advantage of needing no change. Also, in Chinese usage, for anything in the UK, the UK term ought to precede the other. This militates against China-Britain (cf. 3).

6) Britanno-Chinese and U.K.-Chinese are also possibilities, but I find them most unpleasant.

Needham’s use of ‘Anglo’ did however cause problems and is one reason why the Scotland China Association (SCA) was founded by Rev. Ralph Morton; John Chinnery and others in May 1966. However as Needham spoke at its inaugural meeting it should not be considered a break-away group and friendly relations have persisted to the present day.

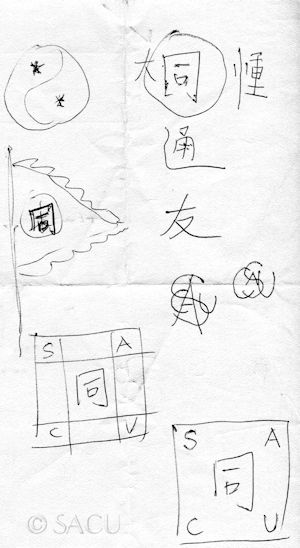

Choosing a logo

Amongst the ‘Needham papers’ are some paper napkins on which possible SACU logos have been drawn out with biro. The eventual winner was the character for friendship (友 yǒu) which was made by the calligrapher Fang Zhaoling. I include one of the napkins, others can be seen online.

Foundation Plans

In early 1965 Roland Berger planned the launch of the new society with Liao Hongying working as a full-time secretary.

One of the first actions was to amalgamate the ‘Friends of China’ groups under SACU. This was fairly urgent because a launch of a National Friends of China was planned for 7th March 1965. In a letter from Needham to the members said: “We feel, however, that in order to avoid misunderstandings, both amongst those working for China and the general public, it would be wise, before any public declarations are made, for FoC and SACU to come together for mutual discussions with the object of arriving at a common understanding and a united body as quickly as possible.”

It was decided that the new society would benefit from sponsorship of many public figures who were broadly sympathetic to the Chinese cause. An invitation letter was drawn up jointly by Needham and Robinson to attract sponsors which states the aims of the organisation: “Our intention is that it would organise public meetings, exchange of visits, film shows, exhibitions and the like. It would provide a forum for the discussion of all aspects of Chinese life, thought and policy. Furthermore, we would aim to get lively branches established all over the country.”

Rough plans for the structure of SACU are preserved on a piece of notepaper. Possible committees included: parliamentary; trade union; scientific; cultural; events; information and finance. SACU would have direct connection to local groups. There would be eminent sponsorship and vice-presidency. SACU would have activities at a high level for trade and foreign policy and maintain relations with the Embassy; organize cultural tours; conference; libraries. A Consultative committee would meet quarterly.

There was debate about who should be invited as sponsors. In an enlightening note from Sir Gordon Sutherland (Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge) to Derek Bryan, dated 9th March, Sir Gordon thinks Spike Milligan and Charlie Chaplin were not appropriate as it “could easily lead to ridicule.”

Positive responses came back thick and fast and an advertisement in the New Statesman on 7th May entitled “SOCIETY FOR ANGLO-CHINESE UNDERSTANDING to provide information; to dispel misconceptions; to create understanding” listed 172 eminent sponsors who had already been recruited. A full list is available to view online. I have added a link to biographies of the sponsors where available. It includes eight MPs; five bishops; 40 professors; 23 knights of the realm; 29 fellows of the Royal Society; actors; journalists and others. I was surprised to find that there are no fewer than 11 Nobel prize winners on the list (Peace:2, Physics:5, Medicine:1, Chemistry:2, Literature:1). Eventually 250 people, leaders in cultural, scientific, artistic and political circles agreed to be sponsors.

The Inauguration meeting 15th May 1965

For the meeting a prospectus was printed setting out the aims of the organisation and included the list of sponsors and a membership application form with a £1 annual fee. It sets out the aims for SACU: “While SACU, as a British organisation, will not identify itself with Chinese policies, it is essential that Chinese views on all matters should be made known. This does not exclude constructive comment and sympathetic criticism. What it will attempt is to foster friendly relations between our countries, making more widely known to the British people the currents of thought and tradition that ran unbroken through the old China, by tracing the transition from the old to the new and by reporting and analysing all the varied elements that make up the totality of present-day China. The study of China’s culture, history, science, agriculture, industry, commerce, politics, education, social welfare and sport illuminates all the aspirations, problems and great achievements of the Chinese people, past and present. Thus we hope that SACU may become a living link which will deepen understanding and appreciation.”

Anticipating quite a crowd, Westminster Church House which overlooks Westminster Abbey was hired. Rooms within the hall were allocated to different functions (sponsors; bookstall; overflow; tearoom). How many people arrived does not seem to have been accurately recorded Tom Buchanan says 600-700 while other sources say 1,000.

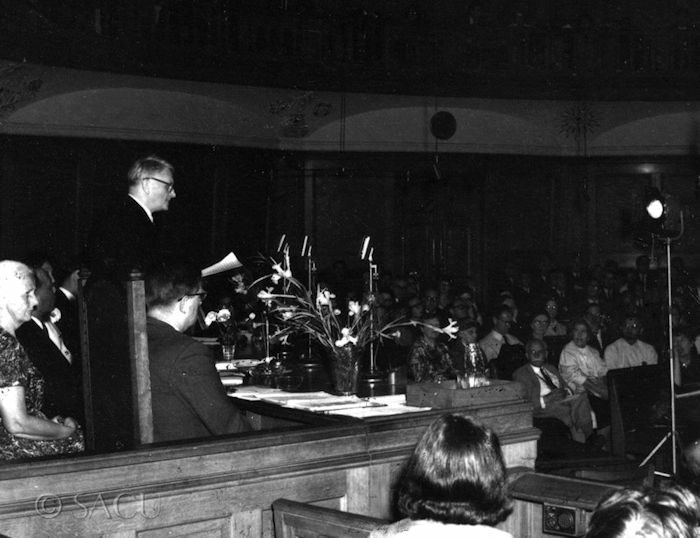

Inaugural Meeting 15th May 1965. Joseph Needham is speaking; Derek Bryan is on his right and Joan Robinson on his left.

We are lucky to have Needham’s notes for the meeting which was carefully planned out. Once again there is not enough space to reproduce the full programme of events; these are available to look at online.

The organisers first met at 1:30 with the press for half an hour; then they were joined by 55 of the sponsors. Joseph Needham then led the sponsors into the main Assembly Room. Messages were read out from those unable to attend including ones from the Bishop of Manchester; Benjamin Britten (composer); J.B. Priestley (writer); the Bishop of Llandaff and Dr. Dorothy Crowfoot-Hodgkin (Nobel prize winner). Needham then gave an opening speech which is available online and was summarized in the first edition of SACU News.

In the speech Needham gave a breathtaking analysis of historical contacts with China he then described the aims of SACU: “The point in a nutshell is that the British people and the Chinese people must come to know each other better. It is urgently necessary for our understanding of world affairs today that the Chinese point of view on all kinds of matters, political as well as cultural, should be made known. We want to do this without preconceived bias or ideological inhibitions, yet not necessarily without constructive bias.”

The Chairman’s speech was followed by a statement by His Excellency Dr. Hsiung Hsiang-hui, Chargé d’Affaires of the P.R.C. During his talk, tapes were played giving greetings from Guo Moruo (Kuo Mo-jo) President of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and from Chu Tunan, President of the Chinese People’s Association for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC). After further messages, Dr. Han Suyin (writer) gave a ten minute speech and then the resolution to formally inaugurate the society was proposed by Joan Robinson. Ernie Roberts (Assistant General Secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers) seconded the resolution.

At 3:47 the meeting was opened for general discussion which lasted an hour. It was Joan Robinson who summarised the discussion and then the resolution to form the society was voted upon and duly adopted. Derek Bryan outlined the planned activities for the first year. Joseph Needham started to wrap up proceedings by announcing people willing to serve on the first Council of Management, these were: Mary Adams; Peter de Francia; Dr. N. Kurti F.R.S.; Ernie Roberts; Vanessa Redgrave; Joan Robinson; Sir Gordon Sutherland; Peter Swann; George Thomson; Dame Joan Vickers, MP; Professor Wedderburn and Dr. Lisowski. He indicated that a Liberal and Labour M.P. may join the committee, which they did and they were Jeremy Thorpe (North Devon) and Philip Noel-Baker (Derby South).

The meeting was then closed with tea available; which at 2/6d a cup seems quite expensive for the time. Those who joined the society were invited to an evening reception.

Aftermath

The press who covered the event were broadly positive, the launch was welcomed by the ‘Tribune’ magazine and it seemed that SACU tapped into a deep well of interest in Chinese culture and sympathy for China’s international isolation that extended beyond the left-wing. Hugh Trevor-Roper, with Arnold Toynbee and Benjamin Britten wrote jointly a letter to the Guardian stating “This society is being formed to foster mutual comprehension between Britain and China in many different fields.”

The Cambridge Varsity magazine covered the event with the title “Caius President leads a new Society. Three heads of Colleges have joined Dr. Joseph Needham, President of Caius in the formation of a new breakaway Anglo-Chinese Friendship Society. The society has had the blessing of the Chinese Communist party.”

However, the press was not universally favourable. The Spokesman Review published in Washington State, USA titled a piece “A New Apparatus Aids Communism … Chief purpose of the new organization, of course, is to feed propaganda to the British people and to the world at large. This will be done through many avenues, in the thin guise of informing the British about the Chinese ‘ideas, achievements and policies… both in history and today.’ Such so-called ‘information’ will consist of a giant drum-beat campaign, in which none of the failures of the Chinese Communists and their system, and certainly no descriptions of their cruelty and oppression as imposed on others, will be mentioned.” The report concludes “It is important that the British and the world at large be aware from its inception that SACU is a propaganda machine for the Chinese Communists, and the joiners will be contributing to that cause and no other.”

From the foregoing pomp and acclamation it must seem a bit of a mystery as to why SACU did not live up to its great expectations. I am reminded of King Arthur’s round table, where the great and the good all subscribed to a noble aim: friendship and understanding; and to stretch the analogy a Sir Mordred was already amongst them. Within a year many of the sponsors had resigned and political, financial and administrative difficulties stymied progress both in China and the UK. However, exploration of this ‘interesting time’ must wait until next year; let us leave SACU after its first meeting forming branches; holding film shows; publishing the monthly ‘SACU News’ and organising pioneering trips to China.